(water)Fall From Grace

The tragic story of the descent of William Mulholland. Once the most revered and powerful man in all of Los Angeles, credited with creating a modern metropolis, his sudden downfall followed a terrible accident—the most deadly catastrophe of its time.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byWillard Simms

The roar burst into the cold winter air a few minutes before midnight on March 12, 1928. Centered about 50 miles north of Los Angeles, it was the last sound some unsuspecting residents of Southern California would ever hear.

The terrifying noise was the result of a man-made disaster, emanating from a huge wall of water and debris crashing down. It was caused by the St. Francis Dam, a massive structure holding back 12.5 billion gallons of water that had burst.

As the formidable force swept through the Santa Clara River Valley toward the ocean, nothing was static. Trees, livestock, houses, cars, bridges, concrete slabs and people were picked up and carried away.

The work camp at the dam’s Power Plant No. 2, a little more than a mile from the failed dam, was one of the first major structures obliterated. Sixty-seven workers and their families were killed.

The towering wave, estimated to be 180 feet tall according to the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, continued rushing down the San Francisquito Canyon to the Santa Clara River. There it turned west, and soon not just camps but entire communities like Castaic Junction and Fillmore were destroyed.

After more than five hours of relentless pounding that left a 2-mile-wide path of destruction, it was over—with the flood finally crashing into the Pacific Ocean between Oxnard and Ventura. Nearly 500 men, women and children—some estimates are closer to 700—were killed.

Bodies were strewn throughout the region, and many had to be dug out of mountains of mud and debris. Some victims were found at sea; others were never recovered. Property damage was estimated at $20 million.

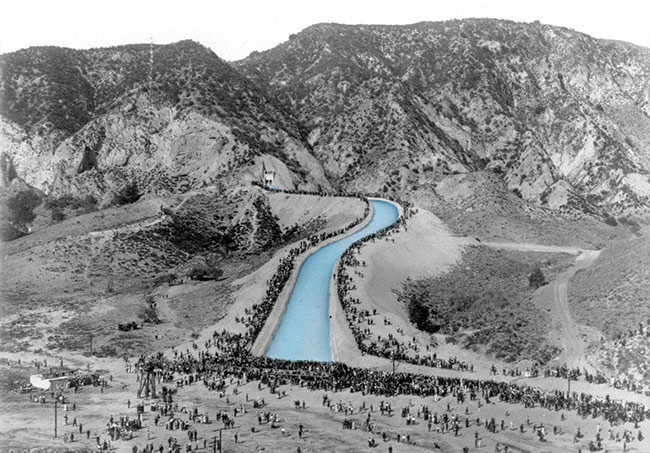

Blame was laid at the doorstep of one person—someone who had been hailed as a leader, even a hero. William Mulholland, the brains and bravado behind the building of the LA Aqueduct … the man credited with bringing water to the area, allowing for propertydevelopment and surging population growth … tagged for the blame. Thousands of Los Angeles residents lined up for the 1913 “Cascades” opening ceremony releasing the aqueduct water.

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Ventura County

When He Was King

It was a dramatic turnaround for the Irish immigrant, whose rise from rags to riches was a tale straight out of Horatio Alger. He’d become a celebrated, prominent citizen—not just in LA but also all over the world.

A straight-talking, clear-eyed “man’s man,” as famous in his heyday as any movie star, Mulholland turned down numerous offers to run for mayor. He palled around with Hollywood A-listers like Charlie Chaplin, and at one point he even had direct access to the president of the United States. He had neither a high school nor college diploma, yet when Life magazine put together a list of “the 100 most influential Americans of the 20th century,” William Mulholland was included.

The Early Years

Raised in Ireland by an stern father and an indifferent stepmother, at the age of 15, Mulholland ran off to sea to join the British Merchant Marines. He arrived to Los Angeles in 1877, when the population was only about 9,000, snagging his first job with the newly formed Los Angeles City Water Company.

The town, still called Pueblo de Los Angeles by some, retained a strong Spanish influence. At the time, the limited water supply for the entire community was delivered from a large open ditch called the Zanja Madre (mother ditch), from which flowed smaller ditches. Mulholland’s first job with the water company was as a ditch tender.

The Ascent

Mulholland accepted the long hours and difficult working conditions, and within a few years was put in charge of overseeing the laying iron pipeline for the community. After more promotions, he had an epiphany.

Los Angeles was growing at a phenomenal rate; by 1890, the population had increased to 50,000. If it kept up, Mulholland realized that soon there wouldn’t be enough water. He and his well-connected drinking buddy and former boss, Frederick Eaton, got the idea of bringing unused water from Owens Valley in northern California south to Los Angeles.

From his ditch work, Mulholland had become a master at making gravity and water work together. He knew that as long as the origination point of the water flow was higher than any point along its route and the route was relatively straight, gravity would take the water to its destination without any assistance.

All he had to do was create a gargantuan ditch that would run the 233 miles from Owens Valley, where the mountain snow melt collected every spring, south to Los Angeles. Eventually, two bond issues were passed. In 1908, Mulholland was placed in charge.

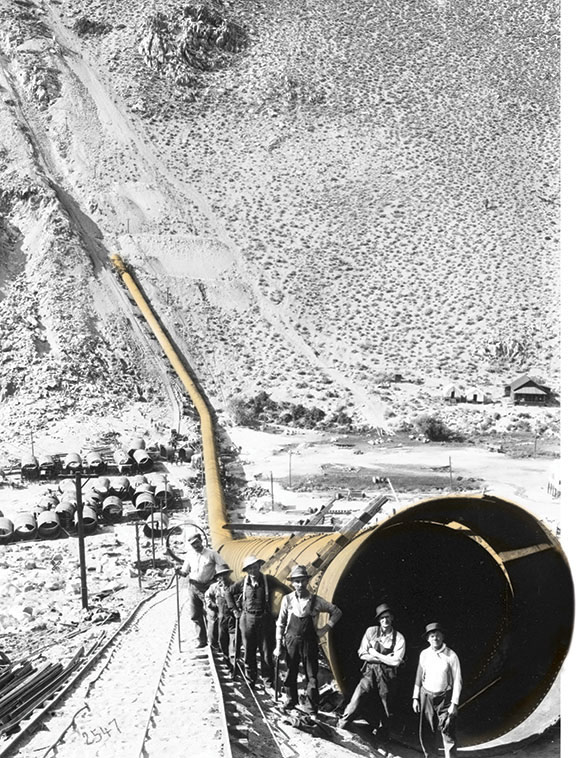

As chief engineer, Mulholland supervised the entire Los Angeles Aqueduct project. By its completion in 1913, he had employed nearly 100,000 men, laid hundreds of miles of concrete and pipe, and built a complex series of tunnels through the mountains. With the new water supply held in a reservoir here in the San Fernando Valley, the population of Los Angeles could now grow by leaps and bounds—which it did.

WORKERS POSING AS THEY LAY PIPE FOR THE 223-MILE-LONG LOS ANGELES AQUEDUCT, THE PROJECT THAT BROUGHT MULHOLLAND PROMINENCE.

The Power of Water

The growing modern metropolis inspired Mulholland to consider ideas to further increase water supply. He thought of creating an enormous reservoir for storage, but a large dam had not been part of his aqueduct system. Getting the thumbs-up to build a reservoir was not going to be easy.

But Mulholland had powerful backing. Some very influential community leaders and businessmen had become incredibly rich from the skyrocketing real estate values the new water supply helped create. They championed Mulholland and the reservoir the same way they had championed the aqueduct.

Among these men were General Harrison Gray Otis and his son-in-law Harry Chandler, who together owned the Los Angeles Times. The Times had endorsed the aqueduct early on. In fact, the Times actually created a “false drought” by publishing carefully manipulated rainfall totals, along with scary articles featuring enormous headlines about the terrible consequences of water shortages.

What wasn’t in the paper was that the Otis/Chandler syndicate was buying lots all over San Fernando Valley. Eventually they became the largest landholders in the Valley.

In the mid-1920s, with California in a terrible drought, the call grew louder to build a gigantic reservoir. General Otis had died, but his syndicate and his Valley real estate holdings had been passed on to his daughter and son-in-law, Harry Chandler.

In 1924, the Times again began to publish frightening articles about the disastrous effects of a prolonged drought, and the Otis syndicate again began buying land in the Valley. Frederick Eaton, who secretly bought ranch land in Owens Valley (much to the dismay of Mulholland) before the aqueduct project had been announced, was also part of the syndicate that bought Valley land.

Most dams built in the mid-1920s, almost 20 years after the Los Angeles aqueduct project had been conceived, were hydraulic fill dams, which were not Mulholland’s area of expertise. But the LA Times kept printing that Mulholland was the only man big enough for the job and that there was no need for outside engineering help.

Beginning of the End

Eventually people listened, and Mulholland got the thumbs-up from the city for the new dam. He decided to model it after the smaller Hollywood Reservoir Dam (later renamed the Mulholland Dam in honor of it’s builder), which had used a concrete gravity arch structure.

The original dam site was further north on the Owens River. But Fred Eaton had already bought the land there and was asking $1 million for it. An angry and frustrated Mulholland then zeroed in on Tujunga Canyon. Word got out, and property values again escalated.

A different site was chosen and this time kept secret. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, this site, in San Francisquito Canyon, was built over an ancient landslide. Years later, scientific analysis proved that to have been a factor in the dam’s failure.

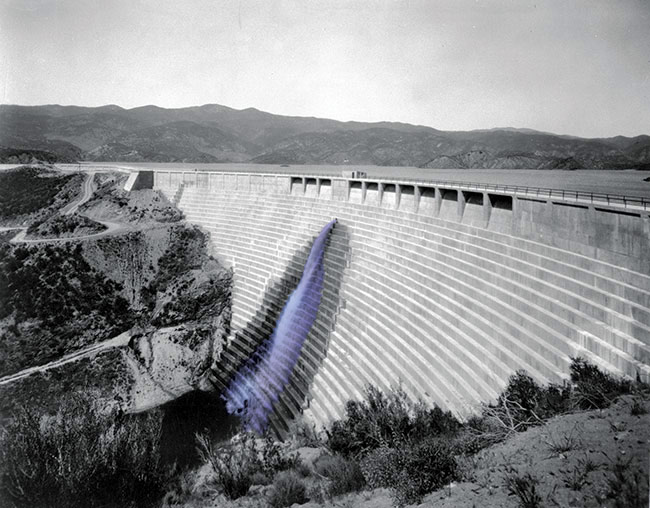

For the first two years of operation, the water filled in behind the St. Francis Dam without problem—stretching out nearly two miles from the dam face. But in the last week before it reached full capacity, small leaks began to appear.

Mulholland announced that leaks were insignificant and part of the process. Within five days of reaching capacity, on a day Mulholland had conducted a site visit, the dam burst.

For Mulholland, the ensuing weeks kept getting darker. Bodies continued being discovered in the Pacific Ocean as far away as San Diego. The catastrophe was second only to the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 in its destructiveness and is still considered the worst man-made disaster in California history.

The St. Francis Dam—before it reached full capacity—in all its glory.

The Final Years

Life as Mulholland knew it was over. While he had always been devoted to his family, he’d had little time for his wife, Lillie, and their five children. Now for the first time since his arrival in Los Angeles, he actually had free time, and he spent much of it with his grandchildren.

But his distinguished career—his lifeblood—was over. He broken-heartedly accepted full responsibility for the failure. During the coroner’s inquest, this man of few words said simply, “The only people I envied in this whole thing are the dead.”

He resigned seven months later and disappeared from public life. He died in 1935 at the age of 79 and thousands filed past his bier in the rotunda of City Hall to pay final respects. His body was entombed in a low-key ceremony at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale.

An inquest jury ruled that no prosecution of Mulholland was warranted. They placed responsibility on improper engineering, design and government inspection. They said Mulholland had no way of knowing the dam’s site contained unstable rock formations, which were ultimately determined to be the cause of the dam failure.

William Mulholland’s reputation has slowly been restored over the passing years. He is commemorated with a memorial fountain in Los Feliz and celebrated with the famed mountaintop Mulholland Drive.

And now, on the 100th anniversary of the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, celebrated by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power this year, the project is still considered one of the great achievements of the 20th century.