PAVE PARADISE … and put up a parking lot?

Power, passion and preservation are all part of a contentious fight in Coldwater Canyon—between the powerful Harvard-Westlake School and a committed citizens’ group—over the school’s expansion plans. Still to be determined: whose roar the city will ultimately heed.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byRachel Heller Zaimont

Exclusive private schools are as familiar a sight as sushi bars in the 818. But few can boast a sphere of influence that rivals that of Harvard-Westlake School.

Forbes ranked the institution the 12th best prep school in the country in 2010, the year it funneled 30% of graduates to the Ivy League or Stanford University. Its roster of alumni features former governor Gray Davis; newly appointed Disney/ABC Television Group president Ben Sherwood; and a slew of Hollywood heavyweights: Candice Bergen, Jenji Kohan, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Jake Gyllenhaal and Jason Reitman, to name a few.

And a powerful network of alumni—including lawyers, entertainment executives and real estate developers—recently joined forces to help elect LA Mayor Eric Garcetti—Harvard-Westlake class of ’88.

But this fall, as students return to the upper school’s manicured grounds, many Studio City neighbors are banding together to fight Harvard-Westlake’s latest expansion proposal. The school wants to build a three-story parking garage topped with an athletic field across the street from its main campus. At a National Night Out block party at the Pinz parking lot in early August, a handful of residents rented a booth—festooned with “Save Coldwater Canyon” banners—to spread the word and add names to their group.

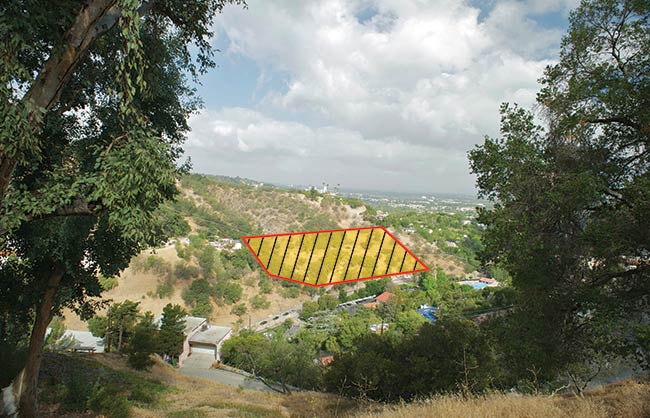

The movement has swelled since the spring of 2013, when Harvard-Westlake unveiled its plan to erect the massive, 750-car parking structure on 5½ acres of school-owned hillside connected by a pedestrian sky bridge over Coldwater Canyon Boulevard. The project would level a tree-covered slope, cut through a protected wildlife habitat and tower over local building height restrictions—stoking the ire of critics who claim it is against the law, as well as their concern that it would mar the scenic landscape.

“They’re going to take away the hillside. We’ll have two years of dust and traffic,” says Jeffrey Jacobs, who lives near the Studio City campus, citing the estimated construction time. “There’s no benefit to the neighborhood that we can see.”

“Having lived through two years of construction for the city’s trunk line project, the last thing we need is more construction,” resident Nancy Mehagian adds. “I love living here. I don’t want to drive down Coldwater Canyon every day and see something that belongs at the airport.”

But school officials say they need the new garage to alleviate a parking shortage that causes students’ and visitors’ cars to spill into the surrounding neighborhood and presents safety issues. “They end up parking along Coldwater and residential streets, creating a situation which is unsafe, congested for commuters and negative for the neighbors,” says Rick Commons, who took over as Harvard-Westlake’s president last fall.

EYE OF THE STORM The proposed three-story garage would be built on a 5½-acre site across the street from Harvard-Westlake, on the west side of Coldwater Canyon.

Some 875 students are enrolled in the upper school this year, which serves grades 10 through 12 on a 19-acre campus that has been updated numerous times since the school’s modern incarnation commenced in 1991. “It has been something the school has needed to do for years. We have had pressures over the years, and they’re building,” Commons says.

Yet as administrators push a plan they say will reduce stress on campus parking lots, a different kind of friction has been mounting between the school and those who live and commute nearby. To some observers, the dispute illustrates LA’s eternal tug-of-war between development and preservation, while others describe a David vs. Goliath struggle, pitting local homeowners against one of the premier prep schools in the U.S.

Some opponents of the plan say they worry Harvard-Westlake will use its wealth and sway to shepherd the project to approval. A group of 1,100 residents and commuters, comprising Save Coldwater Canyon (SCC), are pooling their resources to fight the school’s efforts. As the proposal makes its way through the city’s vetting process, many wonder whether their voices will be heard.

“At what point do you say, ‘No, carving up the hillside is not okay?’” muses Sarah Boyd, who is head of SCC. “Even if you have the money, should you do it? At what point does it stop?”

AN INSTITUTION IN TRANSITION

The controversy comes at a time of change for Harvard-Westlake, with Commons now starting his second academic year at the school’s helm after longtime president Thomas Hudnut retired last summer. Although Commons says he plans to continue many of his predecessor’s policies, some parents say they see a positive shift to loosen the school’s laser-focus on top test scores and Ivy League admissions.

Among the most demanding high school academic environments in the nation, Harvard-Westlake has been criticized in recent years for over-scheduling students with demanding after-school activities followed by countless hours of homework. Commons says he wants to change that.

“It’s hard to make sure the experience is balanced and that there’s room to get enough sleep, to spend time with your family, to spend time with friends,” he admits. “I don’t know that we’ll ever resolve that tension, but trying to make it less tense is a big goal of mine.”

Another goal is to encourage entrepreneurship and hands-on learning—things that “are happening more at the collegiate level than the high school level,” he says.

Harvard-Westlake resembles a small university financially as well. The school has an operating budget exceeding $56 million and an endowment of $64 million. A July post on the school’s blog trumpeted that Harvard-Westlake’s fundraising last year reached nearly $7.3 million—more than any other independent day school in the country.

And in Los Angeles, that money talks. The school was one of the top 10 highest-paying lobbyists in LA in the fourth quarter of 2013, spending $145,385 through two separate law firms to lobby the Los Angeles City Council and the Department of City Planning in favor of the parking structure and pedestrian bridge. Overall, Harvard-Westlake spent $427,678 to lobby the city on behalf of the plan in 2013, plus an additional $80,217 in the first half of 2014, according to the LA Ethics Commission.

“The concern is, residents get the feeling that big money is going to win,” Boyd says.

The school has poured its resources into a series of additions over the years. In 1995 Harvard-Westlake spent $13 million on a state-of-the-art upper school science center. In 2008, despite a protracted fight with high-profile neighbors, the middle school campus in Holmby Hills was dramatically expanded and renovated.

In 2012 the upper school spent $5 million to build a new pool. The parking garage cur-rently proposed would be privately financed to the tune of $50 million.

“There’s nothing wrong with the school—it’s a fine school,” says Susan Jacobs. “But it’s just one thing leading to another, which is really disconcerting. It’s enough.”

A QUESTION OF SPACE

Harvard-Westlake purchased the site of the proposed garage in the 1980s. Over the years, part of the wooded lot has been used for storage and faculty housing; the rest is a habitat for deer, rabbits and birds, billed by the city as “desirable open space.” The land is zoned for single-family homes—two homes on the site were demolished in 2011.

The proposed three-story structure and sports field would feature a protective fence reaching 77 feet to keep stray balls from landing in Coldwater Canyon traffic. The field would be crowned by 10 light poles that rise 84 feet, nearly triple the allowed building height in the area.

To level the hillside for construction, workers would have to remove the equiva-lent of more than 9,000 dump truck loads of soil over the course of one year. More than 100 protected oak and walnut trees would be uprooted, causing a “significant adverse biological impact,” according to an opposition letter from the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy.

“Rarely are big hillside excavations as surgical and tidy as proposed on paper,” the agency cautioned. The school would replace the trees with smaller ones to offset the loss of flora.

But the issue that has community groups most riled up is whether Harvard-Westlake needs the extra parking. The upper school now uses 618 parking spaces—578 on campus and 40 more available free of charge at St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church next door.

In a city report, school officials estimate that fewer than 670 students, faculty and staff park at the school daily. Yet the new garage, along with other campus modifications, would give the school a total of 1,085 spaces. Critics question the school’s push for 400 more spaces than it has drivers.

“We feel like it’s an unnecessary project and that the school has not sufficiently made a case for why they need that large a parking garage,” says Rev. Dan Justin, rector of St. Michael and All Angels. “We support the school in general, but we are 100% opposed to the project as it is.”

Commons says an uptick in extracurricular and highly competitive athletic programs has meant more coaches and visitors are driving to the campus than before. Harvard-Westlake also hosts speakers, concerts and other events.

“Suddenly the traffic doubles,” leading guests to park along local streets, which might compromise their safety, Commons says. “It’s lucky that we haven’t had a tragedy yet.”

Former Harvard-Westlake parent Florence Bunzel says she used to park on Coldwater Canyon when school lots were full. “I have always felt the parking is not adequate,” says Bunzel, a Sherman Oaks resident whose two children graduated a few years ago. “I don’t think anybody would want to see an accident.”

After the inevitable backups caused by construction, school officials say moving bus drop-off from Coldwater Canyon onto the campus would improve traffic flow on the busy thoroughfare. And they believe that added turning lanes would ease congestion at the mouth of the garage.

Some local residents question why the school cannot opt for an alternative plan with a lighter environmental footprint—building smaller parking structures on its current campus, leasing off-site parking with shuttle service to campus or instituting a mandatory carpooling policy, like The Buckley School in Sherman Oaks.

“We have considered lots of alternative designs. This is the structure that we need in order to resolve the parking issues that we have,” Commons says. He describes the added sports field, which would only be used for practice, as essential for the school’s athletic teams. “We think the benefits of this project far outweigh the costs, which are short-term and which we think our opponents exaggerate.”

THE VIEW FROM HERE

Opponents also voice concerns about the school’s potential expansion beyond the parking structure. Administrators say the upper school has no enrollment cap. But according to Commons, there is “no plan to grow the population” beyond about 900 students.

What continues to grow steadily, though, is the land mass owned by the school. County records show the school purchased more than a dozen properties surrounding the campus over the past three decades, including four lots overlooking the proposed garage site in April 2013, the month the project was publicly announced.

In a letter to city planners, the Studio City Neighborhood Council asked the school to provide its 10-year plan. The school has yet to formally respond.

Save Coldwater Canyon has raised funds to commission independent traffic, geological and environmental reports—but their chief weapon is word-of-mouth. Driving on Coldwater Canyon, lawns on both sides of the boulevard are peppered with signs bearing anti-project slogans.

The city planning department is now reviewing public comments on a Draft Envi-ronmental Impact Report it released last October. To go forward, the plan would eventually need approval from city planners and the Los Angeles City Council. Other opportunities for public comment will be scheduled.

“I understand the concerns of the neighbors and want to make sure those concerns are heard and fully considered,” says councilmember Paul Krekorian, in whose district the campus resides. “ will have to respond to every comment given.”

Harvard-Westlake’s supporters are among those speaking out. “They own the property across the street—why shouldn’t they use it?” Bunzel asks. “The school is a vital part of the community.”

But schools operate in residential areas as “a privilege,” based on conditional use permits, Boyd counters. “You can own a property and still have to play by the land-use laws that apply to that property. The school should not get special treatment. They need to follow the same rules as everyone else.”

How the city will vote remains to be seen. “We have a history of cooperating with the city and the community, and that’s what we intend to do here,” Commons says. “We want to be a good neighbor.”