Manny Marroquin has won 17 Grammy Awards for his work as a music mixing engineer—awards that represent collaborations with the likes of Lizzo, Bruno Mars, Jon Batiste, Alicia Keys, John Mayer, and Latin-rock sensation Rosalía. So how many Grammys are proudly displayed in his Larrabee Studios in North Hollywood?

Zero. Not a gold-plated gramophone in sight.

Manny has also mixed for the Rolling Stones, Britney Spears, Kanye West, Miley Cyrus, John Legend, Rihanna, Christina Aguilar, and countless other well-known recording artists. But you won’t see portraits of any of them on the walls. You probably see more celebrity photos at your local dry cleaner’s.

“People think it’s a technical field. Yes, we have tools. But it’s a right-brain process. I don’t approach it as a sonic journey. I go for the emotion. I retain and emphasize emotion.”

Instead, the inside of Larrabee Studios looks like an art gallery. Modern art. Native American regalia. Lush indoor plants. A soothing, restful vibe. The exterior is an unmarked brick façade. All of which belies the fact that Larrabee is one of the world’s most revered sound studios and Manny Marroquin is its owner and resident master.

When I sit down with Manny in Studio 2, his private mixing lair, the reason for Larrabee’s low-key lack of pretense becomes apparent: Manny is low-key and lacks pretense.

This is ironic, of course, in a business populated by giant egos. So one of the first questions I ask is just that: How does he deal with those egos, those demanding creative personalities?

“That may be half my talent,” he replies. “I deal with a lot of insecurity. These artists are like actors. They have to believe they’re the best in the world, but they go to auditions and everyone is turning them down. All that constant rejection. At some point it has an effect.”

But what about all the adulation they receive? “Same. Insecurity and cockiness. They’re both ego.” So obviously, subsuming his own ego is critical for Manny. Two big egos in a mixing room aren’t going to make great music.

Manny’s humility derives partly from his roots. He’s always aware of where he came from, which was from poverty in Guatemala. “I came from a third-world, war-torn country. I never take anything for granted.” He was 9 and didn’t speak a word of English when he arrived in the U.S., legally, with his mom and sister. Music—specifically, playing drums—became his salvation. “We lived in a one-bedroom in Hollywood, and half of it was my drum set. My mom never said that it’s too much.” On the other hand, he adds, “I couldn’t get into trouble practicing drums three or four hours a day.”

Drum practice got him into the Academy of Music & Performing Arts, an LAUSD magnet program at Hamilton High School, but percussion faded to the background when he discovered sound recording and mixing at Hamilton. A mentor there advised him to learn how to make a mean cappuccino—in other words, make himself indispensable at a professional recording studio and learn the trade. That he did, and he worked his way to the top over the course of a 30-year career. Manny, who lives in Toluca Lake near his studio, has been married to talent manager Terrie Marroquin for 20 of those years and is the father of two young adults.

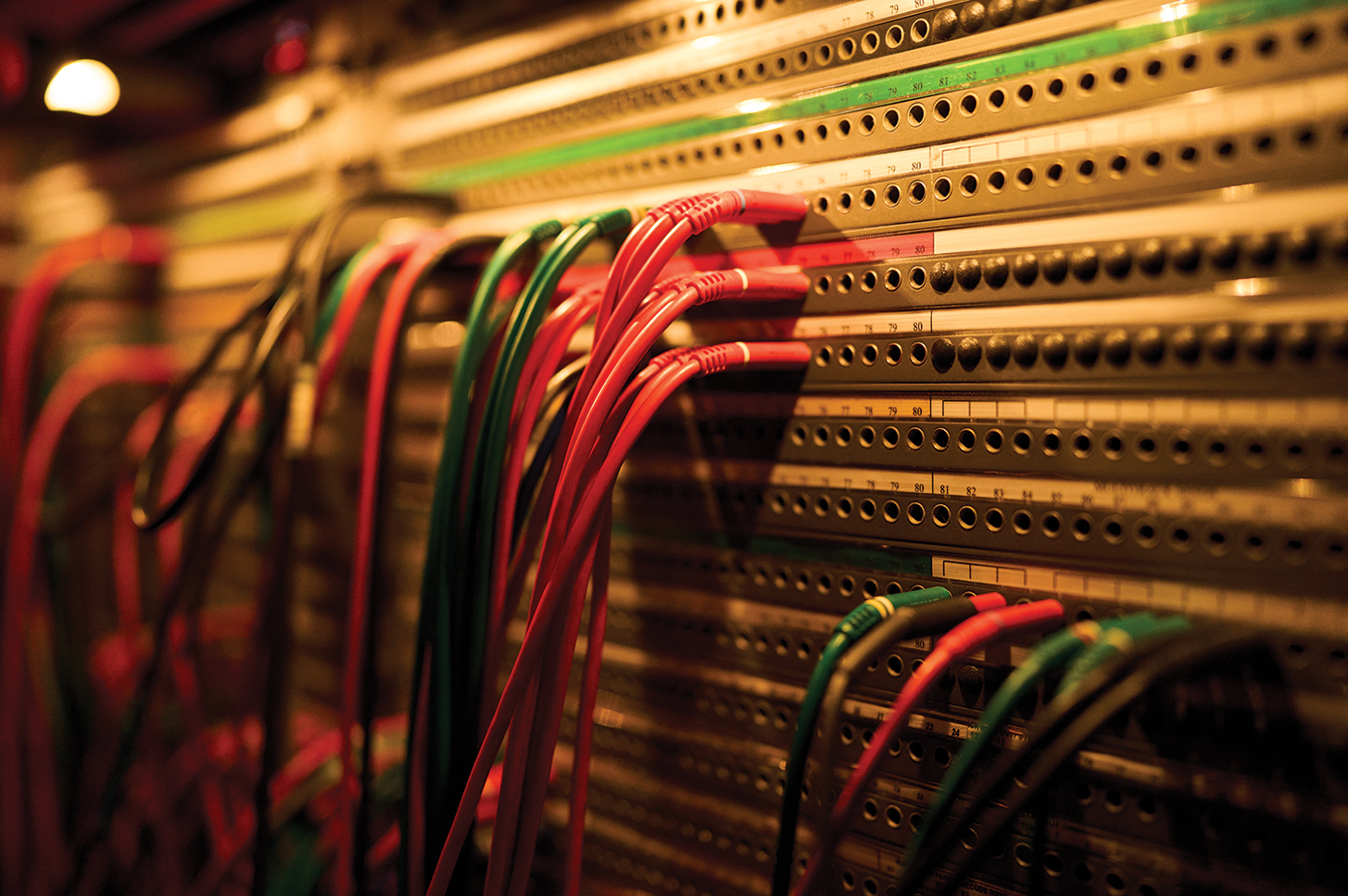

Another reason for Manny’s lack of pretense lies in the very nature of sound mixing. On a literal level, a mixer takes recorded tracks and combines and adjusts them. Those tracks come to him from the artist and/or their producer, each track recorded independently. As a mixer puts them together, he or she adjusts sound levels, equalizes tracks to boost or cut frequencies, removes hisses, adds effects like reverb or delay, compresses sound to make it more consistent or more even—all manner of magic. It all has to do with mastery of the million knobs and switches on the studio consoles at Larrabee, which to a nonprofessional look like Mission Control.

But as I mentioned, that is the literal level, and Manny barely touches on that in conversation. Obviously he knows the technology. He’s developed some of it, in fact. But Manny’s creative talent lies in understanding emotion. He keys into an artist’s emotional intent. “People think it’s a technical field,” he says. “Yes, we have tools. But it’s a right-brain process. I don’t approach it as a sonic journey. I go for the emotion. I retain and emphasize emotion.”

And therein lies an extraordinary creative process that Manny hopes none of us will ever notice or talk about. He explains it with analogies. “It’s a roller-coaster. You don’t want to just go up. And you don’t want to only drop. Going up is the anticipation—up, up, and … drop. That’s the push-pull of emotions. To me, they are frequencies. That’s what we do in a song.”

None of this has anything to do with adding sounds or changing the music in any way. He completely honors what his artists and producers bring to him. “We’re here to serve them. It’s their vision.”

Manny adds a corker that really underscores his humble nature: “You should never listen to a mix. You shouldn’t have to think about why you like it. Our job is to make sure you don’t notice. I want you to hit repeat, not the next button.”

Today Manny not only owns Larrabee Studios, but is also one of five investors at Verse next door. Verse is a sophisticated supper club with, no surprise, live and recorded music, an extraordinary immersive sound system, and exceptional acoustics that make both listening to music and conversing with companions a pleasure. “We don’t publish or push out who performs each night. We carefully curate the artists, and it is often done last-minute. I want people to trust us; they come here for an extraordinary evening, and they know whoever is playing will be great.”

Verse even has its own mixing engineer on hand to tweak sound levels. No, it is not Manny. But in addition to helping manage Verse, he does have a music-related role there. He creates the playlists, which run six to seven hours long. The guy who spends his days mixing music spends his evenings curating music. “With a nice glass of wine. It’s some of the most fun I have.”

Painter and Sculptor Charles Fine Says Growing Up Valley is a Major Influence in His Art

Indelible impressions.

Join the Valley Community