On a December afternoon in 1974, a 10-year old boy, out of school for the holidays, walks from his home on Valley Vista Boulevard in Sherman Oaks to the La Reina Theatre on Ventura Boulevard to see a Brian DePalma movie. The boy is Bret Easton Ellis, and the movie is Phantom of the Paradise.

Le Reina Theater in Sherman Oaks opened in 1938. Later it was purchased by the Mann Theatres chain, and continued to show first-run movies until closing in 1986. Photo courtesy of Bison Archives.

“I saw it,” Bret explains, “because I had read Pauline Kael’s rave review in The New Yorker, and I became obsessed.”

A 10-year old reading a review by The New Yorker’s highly respected film critic? Precocious, indeed.

Bret is well known as a novelist (Less Than Zero, American Psycho), a screenwriter (four of his books have been made into movies), and an astute observer of film, TV and pop culture. A lot of that makes its way into current endeavors like The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast. Talk to him about growing up in the Valley and he points to movie theaters, saying that they were a big part of his Hollywood education. As he delves further into the subject, one begins to get a picture of a time and era that no longer exists.

“Movies in the ’70s had to have a realistic ending. If you didn’t deliver that, you were coddling the audience and the audience rejected it.”

Back then single-screen theaters thrived, tickets were cheap, and movies were risqué, a result of relaxed censorship in the industry. Kids had a lot more freedom to check out whatever was playing without much, if any, supervision. Helicopter parents were nonexistent. When parents did bring their kids to a popular R-rated movie, it was no big deal. At least not in Bret’s family.

“My mother took me to a theater in Studio City to see Saturday Night Fever (back in those days, a hard “R” thrill) when I was 13, he recalls. “She had a crush on John Travolta and had been playing the movie soundtrack in her car for two months.”

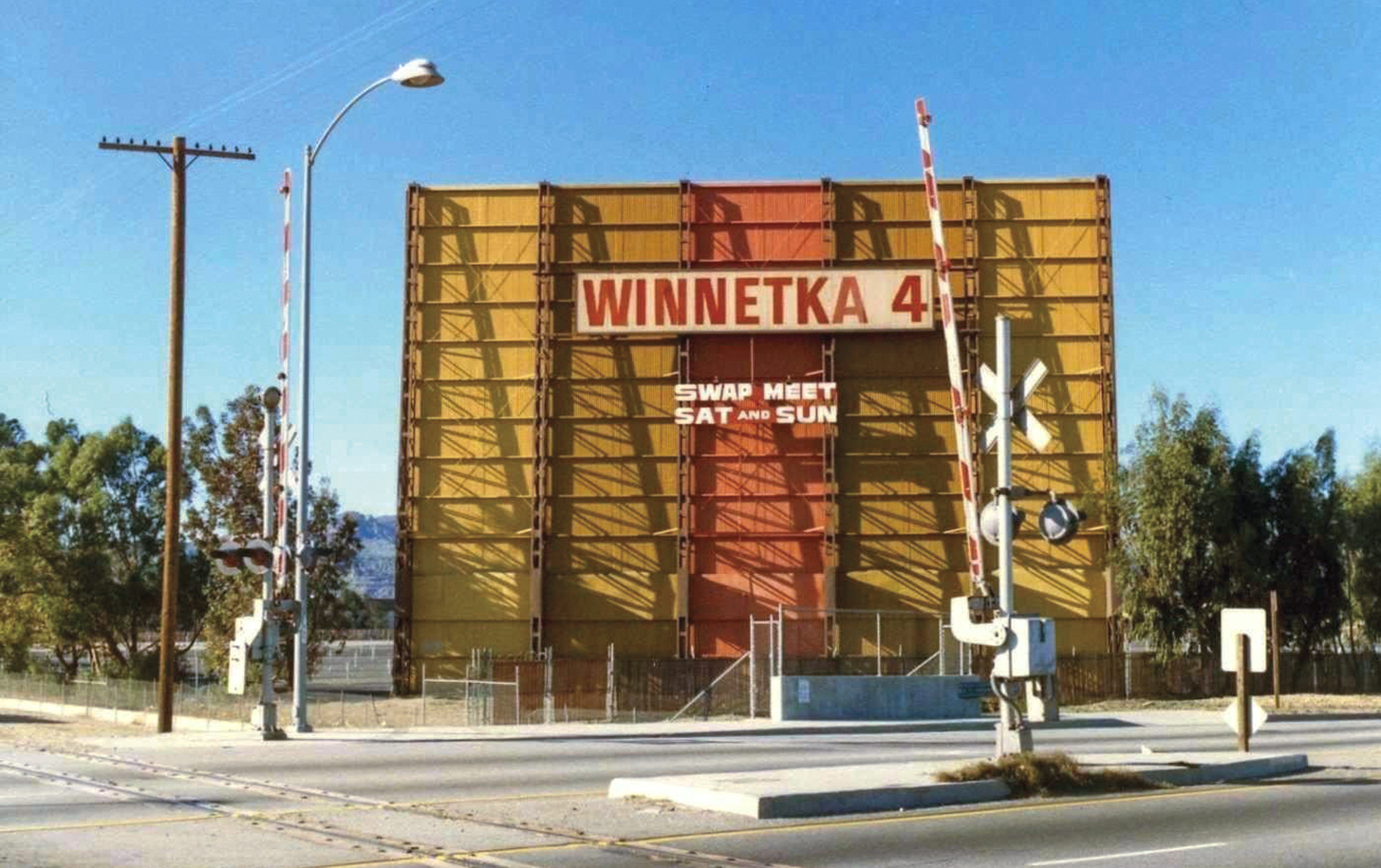

One of two screens at the Winnetka Drive-In in Chatsworth. Photos courtesy of the Valley Relics Museum.

Bret remembers the ’70s as a time when every neighborhood along the Boulevard, from Studio City to Woodland Hills, had a theater. While some had design flourishes like art deco neon marquees, none came close to the opulent glamour or historic relevance found on the other side of the Hollywood Hills. Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, with its Revival-style architecture, was the most famous. But there were also noteworthy theaters in Westwood, known for design splendor as well as for hosting star-studded, red-carpet premieres.

Though Valley theaters couldn’t compete with those movie houses, they did offer something unique: space. Land was plentiful and inexpensive, and drive-ins dotted the Valley basin. Parking in front of a big screen allowed parents to watch the latest edgy films while their kids slept in the back seat. Or in Bret’s case, pretended to be sacked out.

“When my parents went to see M*A*S*H, they thought my sisters and I were sleeping. I was kind of watching the movie, and then I noticed that there was another drive-in; I think it was called the Winnetka. There were actually two drive-in theaters, one facing one way, one facing the other way, and A Clockwork Orange was playing on the other screen. “I’m like 6 or 7 years old, looking at both these movies, and my mind was being blown.”

It was a time when movies intended to shock the audience out of complacency, and even kids sensed something exciting was happening on those big screens. More importantly, something real. Something visceral.

“Movies in the ’70s had to have a realistic ending,” Bret explains. “If you didn’t deliver that, you were coddling the audience and the audience rejected it. They were hipper than that. In the era of Nixon and Viet Nam, they knew that everything was a scam, and everything sucked, and that was kind of the mood that we grew up in.”

The other of two screens at the Winnetka Drive-In in Chatsworth. Photos courtesy of the Valley Relics Museum.

But outside the theaters, especially in suburban bedroom communities like his hometown of Sherman Oaks, neighborhoods seemed safe, and all appeared well. For a precocious thinker like Bret, already one who noticed the split between residential normalcy and, as he puts it, the “dysfunctional gray zone” that simmered beneath, horror movies became his comfort zone.

“These films were not only a confirmation but also a reflection of what was going on in my world,” he continues. “My parents were fighting and on the verge of divorce, my father’s alcoholism, my realization that I was gay—all of these things entering into what was supposed to be, at least on the façade, the American family with a stay-at-home mom, the diligent dad that went to work every day, the two sisters, the boy.”

In the Valley, Bret could sample the full horror menu, from the vicious Theatre of Blood starring Vincent Price to the macabre Tales From the Crypt series. He watched Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things, a low-budget zombie film, at a theater in Northridge; and of course, Brian De Palma’s rock-horror musical Phantom of the Paradise, which featured plenty of blood and outrage and marked a turning point for Bret. “Watching Phantom was the moment I knew I was going to be a writer.”

Perhaps not a conventional Hollywood education, but for Bret, an inspiring one.

Chloe King and Carol Wolper are working on Hollywood, North, a book that examines the San Fernando Valley’s often-underplayed role in film and TV history. Over the next several issues of VB we’ll share, as we did with this article, excerpts from some of their interviews for the book.

Join the Valley Community