The Executive Director of the Soraya Reflects on a Year Without Live Performances—what It Has Meant to Artists and to the Human Experience

Intermission.

For the past seven years, I have worked at The Soraya, a bustling arts center on the campus of California State University, Northridge. Nowadays, the occasional visit to my office feels like something out of an eerie movie—166,000 square feet, typically buzzing with activity, now stands as a time capsule. The March sales report sits atop my in-box, and playbills from canceled performances are stacked in piles for audiences that never came. I check the mail, water the plants and make a trip around the building to ensure everything is secure.

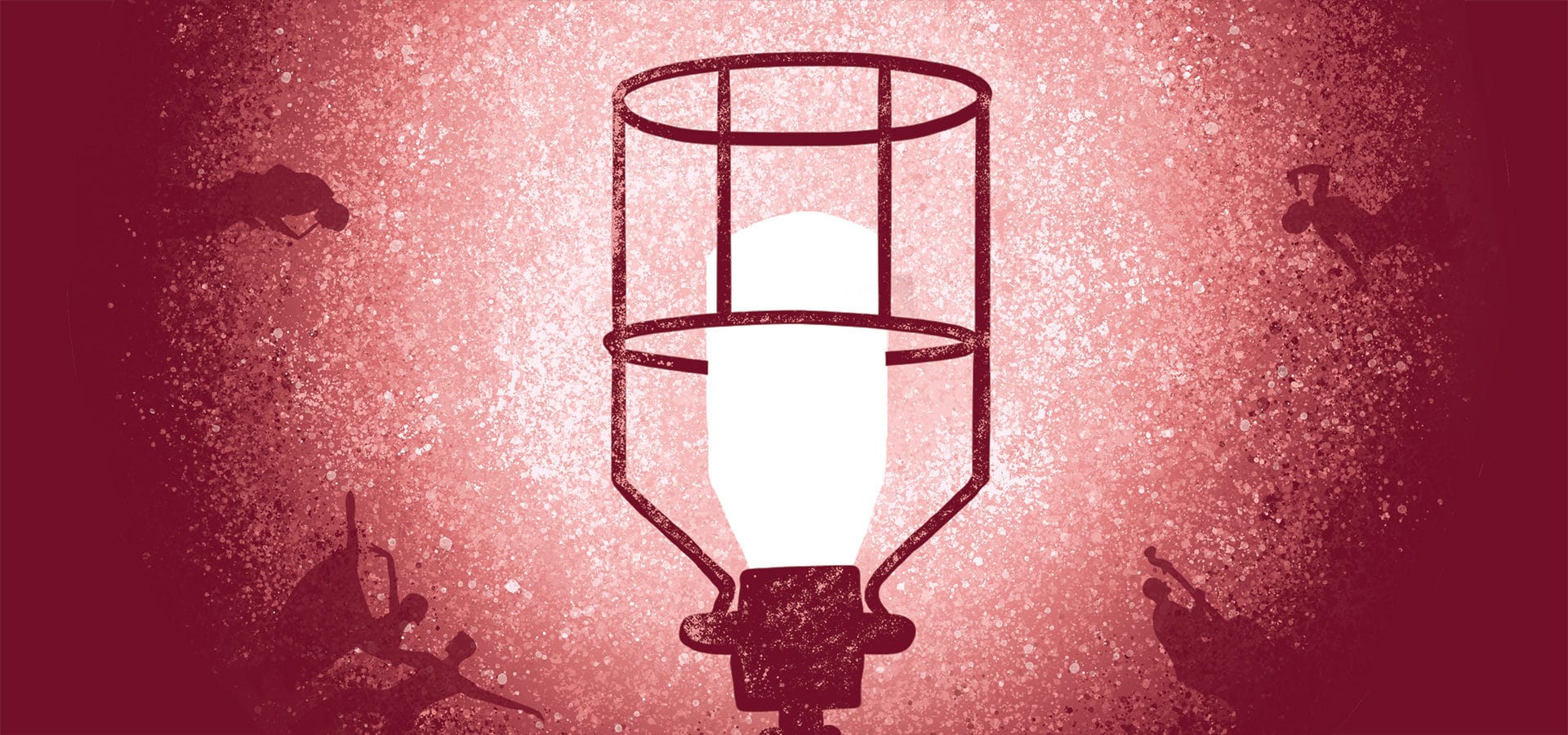

The dressing rooms are scrubbed clean but lifeless. The expansive stage is supervised by a single naked lightbulb. One can’t help but be struck by the contrast: Normally a blank stage holds anticipation, awaiting the next troupe that will arrive to magically transform it. The shades on the ticket office windows are pulled low. The courtyard is populated by a single underweight squirrel accustomed to handouts. Though I’m empty-handed, she goes toe to toe with me and stands tall to inquire anyway.

The lobby is the final stop on my rounds. Here I pause. The emptiness is piercing. Without an audience, there is no art. Without an audience, it isn’t only the business of the arts that is impacted—it’s the artists themselves who suffer, denied their livelihoods and perhaps more so, their purpose. Many artists see themselves as frontline workers of a different sort, coming from a long lineage who respond to history with the power of imagination, and who tend to the soul of a community of friends and strangers in a collective ritual that is nonpartisan, nonsectarian, nondenominational.

I have dedicated myself to this vision for three decades. In the 1990s in San Francisco, I joined other artists in responding to the AIDS crisis. In 2001 in New York City, I heeded the rally cry to reopen theaters following 9/11. A decade ago, I joined fellow organizational leaders in a collective belt-tightening during the Great Recession.

While those crises were difficult, they pale by comparison to today’s, especially as experienced by artists worldwide. The majority have been totally without their livelihood for nearly a year. Who could ever have imagined a total global halt to live performances? Many of us met the moment by pivoting to online performances, efforts that yielded some positive results. However, great performances are not meant for small screens and unstable internet connections.

Artists bring people together, but in the past year the best we could do was diligently keep ourselves and our audiences out of harm’s way. Like everyone, I now spend my solitary days on Zoom where I strive to keep my organization afloat and do my best to offer some relief for a few of the tens of thousands of artists who are without any income.

My rounds at work complete, I leave the theater, merge onto the 405 and head toward home. While artists and those of us who support their work were not considered “essential” during the pandemic of 2020, I do imagine a moment when that changes; when the pandemic recedes and theaters reopen; when Angelenos emerge from their homes is search of renewed human connection. I am strengthened in my resolve to be on the frontlines of the recovery, to offer the joy of concerts and performances, to do my part to revitalize the economy, and to put back to work creative professionals who make it their mission to uplift humanity with beauty, inspiration and joy.