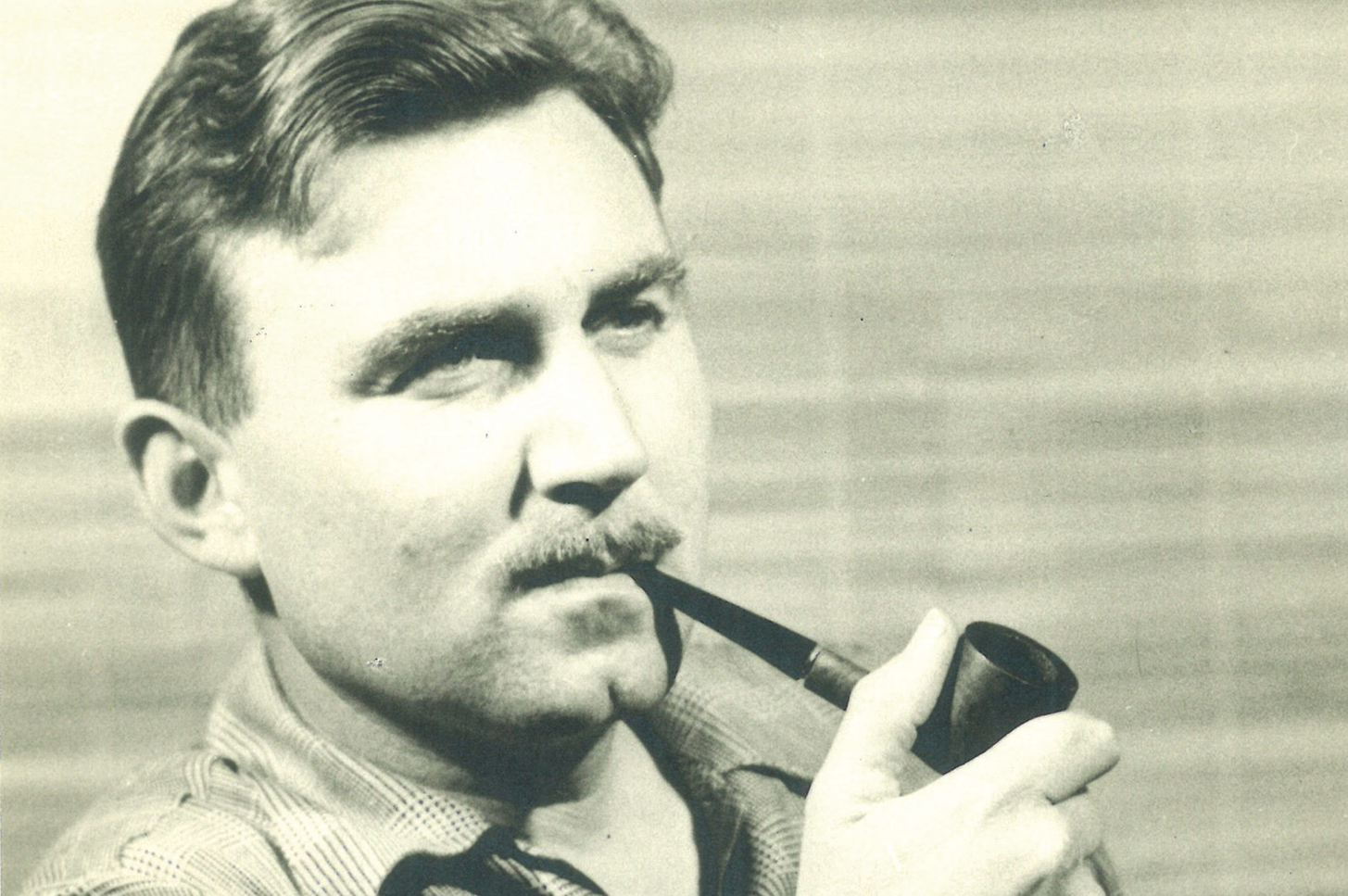

“His mind was like a camera.” That’s how Paula Kiechle Kerris describes her father, artist Edgar O. Kiechle. Her sister, Suzanne Kiechle, calls him “Mr. Observation,” adding that he even painted what he saw in his car’s rearview mirror. None of this comes as a surprise to anyone who has beheld Edgar’s oil paintings, many of them beautiful testaments to life in the San Fernando Valley in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

View of Ventura Boulevard by night, painted in the 1950s

“His mind was like a camera.” That’s how Paula Kiechle Kerris describes her father, artist Edgar O. Kiechle. Her sister, Suzanne Kiechle, calls him “Mr. Observation,” adding that he even painted what he saw in his car’s rearview mirror. None of this comes as a surprise to anyone who has beheld Edgar’s oil paintings, many of them beautiful testaments to life in the San Fernando Valley in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

“He had a great sense of storytelling through his art. He captured heart and soul in his paintings,” says Paula.

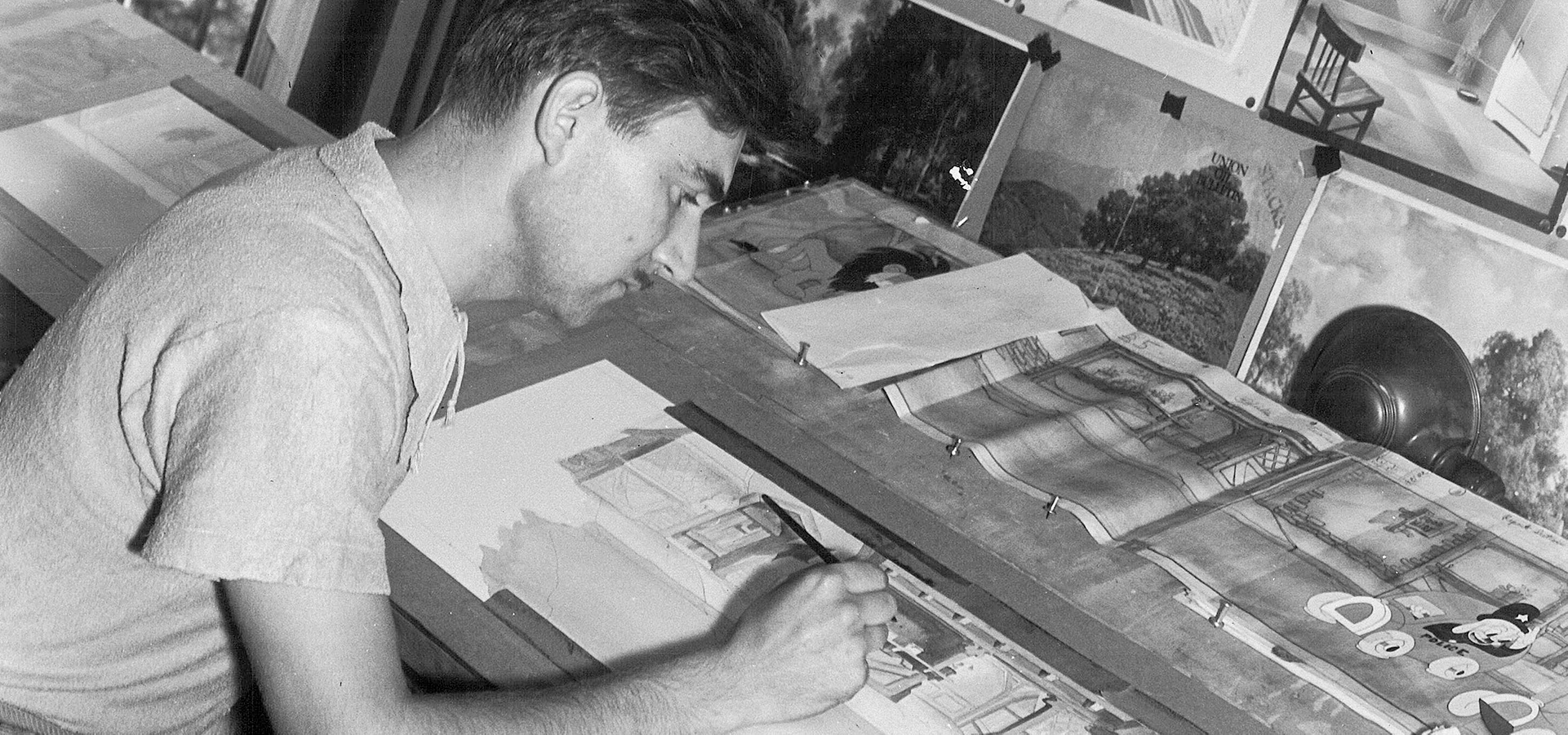

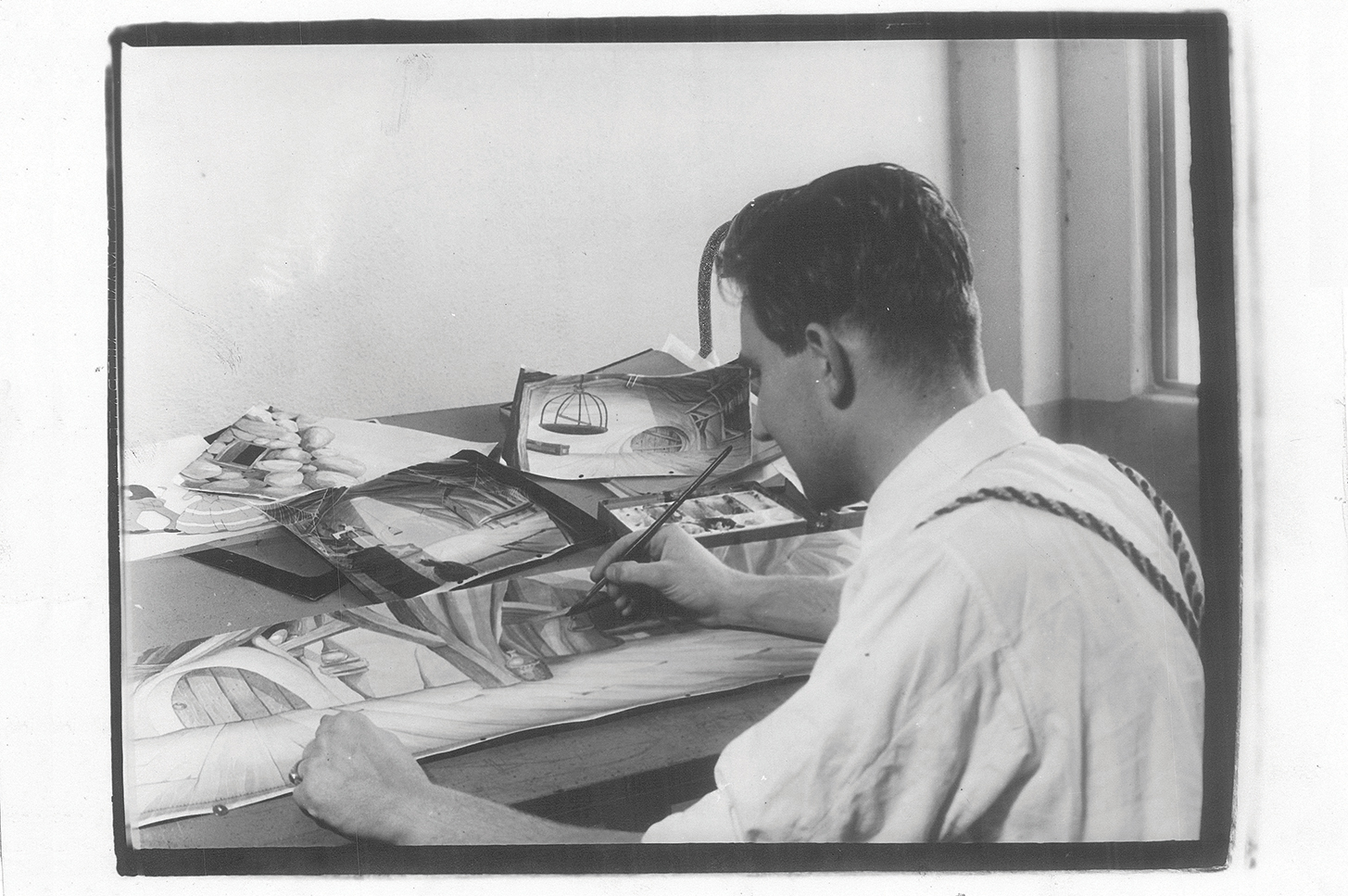

Life for Edgar began in the Midwest. He was born in Missouri in 1911. When he was 8 years old, his father, Anton, moved the family to Hollywood to pursue his career as a stained-glass artist, followed by stints painting backdrops on silent films.

Another view of Ventura Boulevard by night, also painted in the 1950s

Years later, Edgar, following in his father’s footsteps, attended Otis College of Art and Design. Though he studied architecture at the time, his keen abilities as a fine artist would ultimately dictate his future.

In the early 1930s, Edgar landed a job in animation at UB Iwerks. When that studio closed, he moved on to Walter Lantz Productions, and then Universal Studios. By the late ’30s, Edgar’s detailed and vibrant brushstrokes put him on the map as an illustrator.

His years creating cartoons turned out to be a launching pad for his work as a set designer on feature films, many of them classics. While Edgar got jobs at all the studios (the majority were in the Valley, known then as “Hollywood North”), Universal was his steadiest client.

Above: Paula Kerris and Suzanne Kiechle in the garage of the family home with some of their father’s paintings

•••

In 1936, Edgar made the decision to move with his wife, Beatrice, from Hollywood to Studio City. Because the LA River was not yet concrete-lined, Edgar purchased a plot of land on higher ground, which proved to be a prescient move. Two years later, LA was hit by the biggest flood in its history, killing more than 100 people.

The family settled on a quiet street just off Laurel Canyon, surrounded by walnut groves. He and Beatrice would go on to have three daughters, one of whom, Suzanne, still lives in that Studio City house. Except for the walnut groves, the property remains much the same, and includes Edgar’s makeshift studio in the garage, still filled with paintings, drawings and storyboards.

A Valley streetscape at night, painted in the late 1940s

Edgar rose in stature and notoriety, particularly at Universal, where he’d spend his lunch hour sketching whatever struck his fancy. Mr. Observation, the man with a mind like a camera, captured everything from the mundane to the extraordinary, starlets among them.

After actress Ida Lupino commissioned him to do a portrait of her sister, the word got out. Soon, lyricist Ira Gershwin, screenwriter-director Preston Sturges, and a slew of other luminaries were hanging Edgar’s work in their homes. Hedy Lamarr, who owned one of his pieces, hosted a show for him. By the 1950s, Edgar’s paintings hung in galleries around the country, including Elizabeth Taylor’s father’s art gallery in Beverly Hills.

Meanwhile, Universal, having amassed a large collection of the artist’s works, began to rent his oil paintings out to Hollywood movies, most notably An Affair to Remember (1957), Imitation of Life (1959), Pillow Talk (1959) and Magnificent Obsession (1963). On the set of For Love or Money (1963), where one of Edgar’s paintings was hung behind him on the set, Kirk Douglas was heard joking, “I’ve never been upstaged by a painting before.”

His artistic sensibility and passion grew with each passing year. Having adopted a service dog while serving in World War II, he would spend hours walking his pup along Valley streets, all the while clocking every detail of his surroundings. Later he would set those observations down on paper and canvas.

A man sitting at the foot of the hills in Studio City, painted in the 1950s

While the major cities of the world have been captured on canvas since time immemorial, it can be challenging to find renderings of the San Fernando Valley. There are historical photographs, yes, but nothing conjures life in the Valley during gentler times quite so vividly as Edgar’s vivid treasure trove. A nightscape of the Cahuenga Pass. A bustling night scene of Ventura Boulevard in Studio City at Christmastime. A young girl—a friend of Paula’s—sitting on the banks of the LA River at the corner of Laurelgrove Avenue and Valleyheart Drive. “She was mourning the loss of the wooden bridge that was washed away in the flood. It used to be our gateway to the movie theater and little Kiddieland amusement park, which we’d frequent on the weekends,” recalls Paula.

While Edgar created set designs for scores of well-known films, his motivation was not money or prestige; it was simply to create.

“His true passion was his art,” says Paula. “He’d take on a commercial ad job, an architectural job, a portrait for a movie—wherever they needed his help. All on the side. He was the guy who was always in the background, expressing himself through his brush.”

Tragically, just as he was hitting his stride at age 49, it all ended. Working on the set of The Last Sunset (1961) in Mexico, Edgar contracted dysentery. He came back ill, and his doctor told him to go home and rest. “He walked in the door and collapsed right here,” says Suzanne, pointing to the floor in the living room.

Edgar’s paintings remained at the Studio City home for nearly four decades, until Beatrice died in 1998. The sisters were stunned when they started to catalog the works. There were nearly a thousand pieces. They wanted to keep the paintings together as one collection, but at the same time, “We wanted to get his name and his art out there,” explains Paula. When keeping the collection whole turned to be a challenge, they decided to sell some of it. Art dealer Jim Waterbury bought about a hundred pieces, some of which will be showcased in the Palms Springs Modernism Show at the Palm Springs Convention Center, February 16–20.

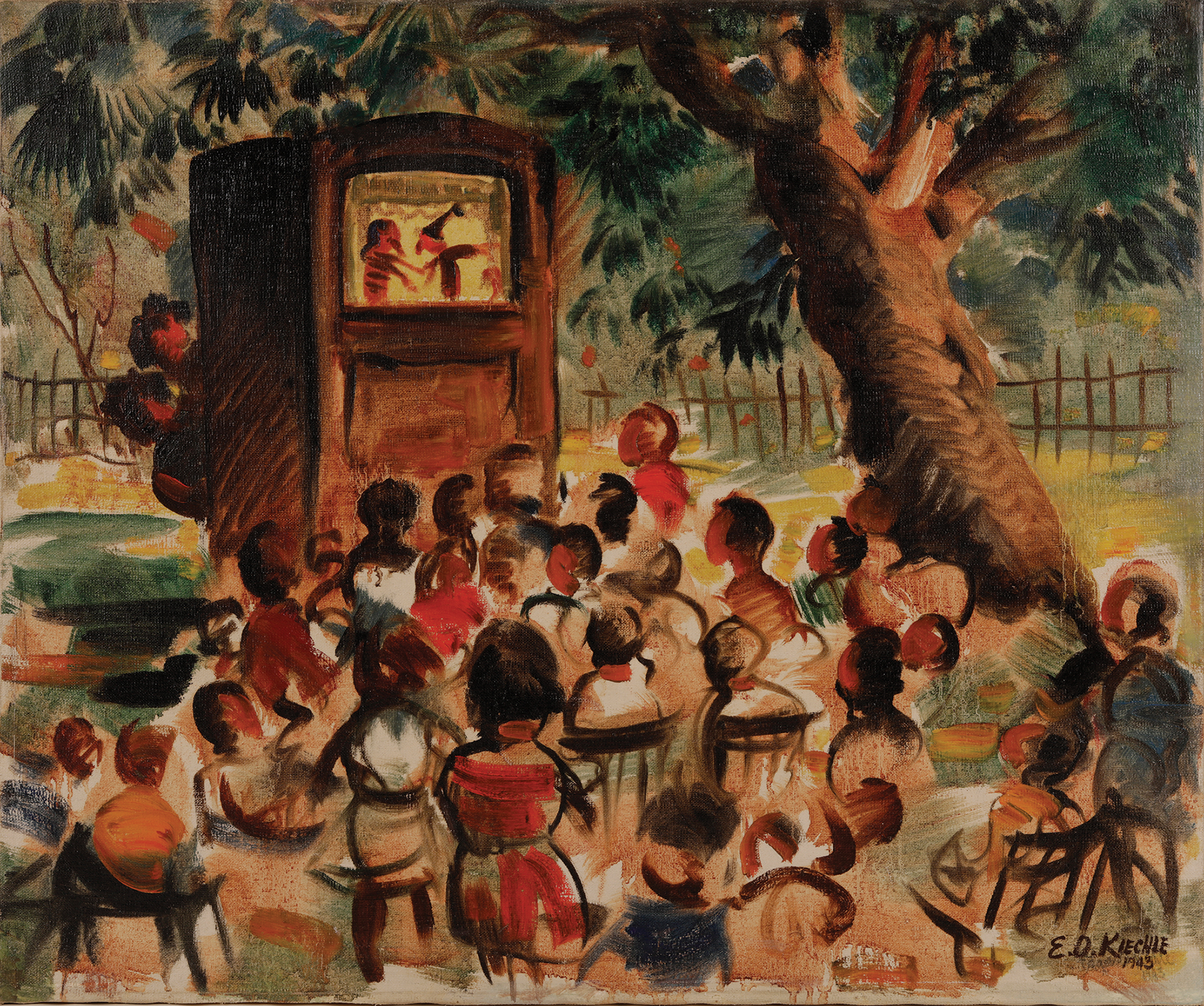

“Puppet Show in the Park” (1945) shows children riveted by a performance on a tiny stage at North Hollywood Park—a scene that could have been straight out of one of Edgar and Beatrice’s real-life puppet productions. He made the puppets, while Bea, a pianist, played the music and voiced the female characters. Together the duo performed in parks and schools all over the Valley.

“What I like most about his painting is his ability to capture the mood of a specific time and place,” says Waterbury. “His works in the ’40s and ’50s depict a still slightly rural LA as it is growing into a major city. His paintings along a bustling Ventura Boulevard beneath the still-wild Hollywood Hills are among my favorites. He documented the emergence of the area as few have.”

Paula and Suzanne are delighted that their dad’s paintings are seeing the light of day, displayed in the homes of people who appreciate them, just as they do.

Above the fireplace, in the living room where Edgar collapsed, hangs a striking portrait of a little girl. “That is me when I was younger,” says Suzanne. “I love seeing it there every day.”

Join the Valley Community