The Wild West

Reflecting on growing up in the ‘70s in Calabasas where much has changed—yet some of the simplest joys remain the same.

At the age of 7, on most days I could be found running up Venice Boulevard, across from Venice High, in polyester shorts with a quarter to buy an Abba Zabba at the neighborhood liquor store.

Then my world was torpedoed. Three days before my eighth birthday, my parents plucked me from my asphalt wonderland to move to a place called “the valley” and a town named “Calabasas,” which I learned meant pumpkin in Spanish. I was devastated. My mom made her case, “You’ll have your own room.” Nope. “The house has stairs.” Nope. “There will be horses.” Hmmm …

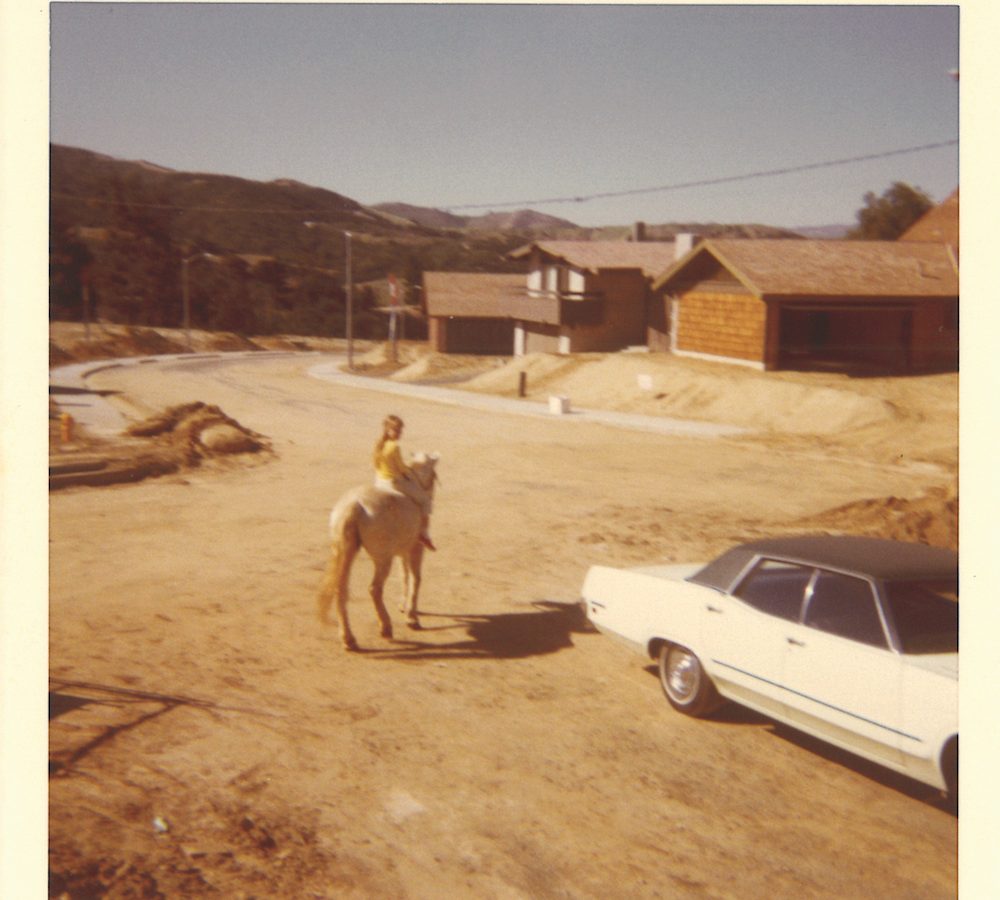

We bumped up the dirt road that was to be my street. At the top were three new homes that looked similar. These were called “tract homes,” and our tract was called “Braemar.” It was the middle of nowhere—mostly fields. I wanted to go home, but this was home.

Our new house was next to what is now Calabasas High: rolling hills, horse trails, 100-year-old oak trees and a creek—perfect for catching pollywogs. It wasn’t long before my life was filled with wonder and discovery.

Wild overgrown fruit trees from the ghostly remains of the Jack Carson ranch were a wonderful source of snacks for us roaming kids. We could jump on a horse and ride bareback and barefoot. Stepping on a rusty nail was a right of passage.

We caught lizards in coffee cans, snakes with our bare hands and secretly fed the rabbits that gnawed on vegetables from my dad’s garden. The night was a symphony of chirping crickets, baritone toads, singing coyotes and stars.

I remember the African daisies that followed the sun and went to bed with the moon. I still feel the wet purple lupine and the smell of wild mustard that didn’t taste like mustard at all. And if a California poppy reflected orange under your chin, it meant you were pretty. I wasn’t pretty, but the poppies told me otherwise.

At the bottom of our street was “Park Modern” where all the streets were named after birds. It was an older community where the “artsy” people lived. Jimmy Durante lived there and would finish his shows with “Good night Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.”

Nearby was a makeshift hippie colony. Whispers went through our wolf pack that Charles Manson once lived there. We stayed away. Hippies scared us. Even scarier was the long-abandoned bomb shelter, deep in the brush. We were certain it housed devil worshippers at night. On serious games of hide and seek, I’d end up in that bomb shelter—cool, dark and quiet with graffitied walls, cigarette butts and thin, quarter-size plastic wrappers—I assumed from the devil worshippers.

Old Calabasas was a tourist attraction with an authentic general store and a haunted mansion called Leonis Adobe. Not far off was a man-made lake surrounded by houses where the “rich people lived.”

We’d walk to Alpha Beta to buy pop rocks, ride bikes to the Valley Circle Theater and buy the best ice cream ever at “Sav-On” for 25 cents a scoop, long before the likes of Sweet Rose Creamery or Salt & Straw.

I was the queen of my imagination, a sun-browned wild child with dirty feet and skinned knees, whose greatest worry was losing a kick-ball in a cluster of tumbleweed. No need to go home until the African daisies went to sleep.

But things changed as they always do. Houses built, streets poured and then schools, malls and restaurants. The Wild West gave way to urban sprawl.

Yet given a perfect hike on a perfect day, my daughter and I can still find wild mustard to smell, feel the wet purple lupine and hold a magical poppy under her chin to tell her she’s pretty. And I promise her that no matter how much the world transforms—out there, somewhere—there will always be horses.

Discover 5 Heat-loving Greens for the Valley Summer Veggie Garden

And you thought it was too late…

Painter and Sculptor Charles Fine Says Growing Up Valley is a Major Influence in His Art

Indelible impressions.