A Tale of Two Isaacs

The story of two pioneering men—named Lankershim and Van Nuys—and how they turned a 60,000-acre cattle ranch into a sea of wheat … and ultimately the San Fernando Valley.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byNathan Masters

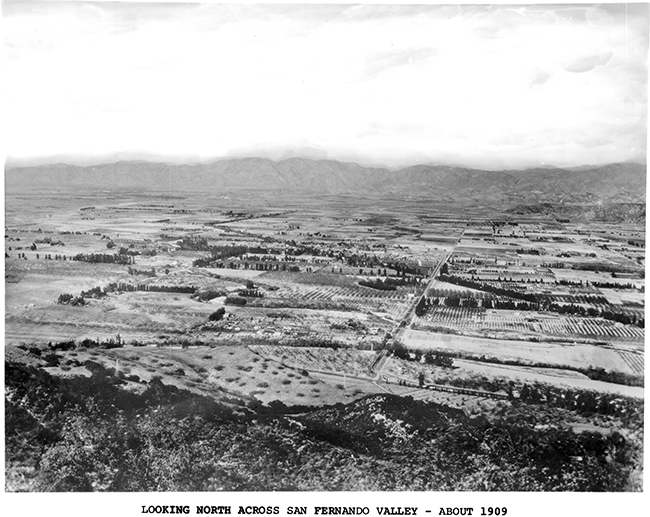

Stand atop the crest of the Santa Monica Mountains on Mulholland Drive, and the San Fernando Valley unfolds before you. Houses, swimming pools, apartment buildings and strip malls extend in a grid-like pattern over the plain.

But long before the San Fernando Valley became suburban—before water from the Owens River cascaded down the Mulholland spillway, before real estate investors and electric railway barons subdivided the land—almost the entire expanse of the Valley was a giant field of wheat. And two men named Isaac owned its southern half.

Meeting in a Faraway Valley

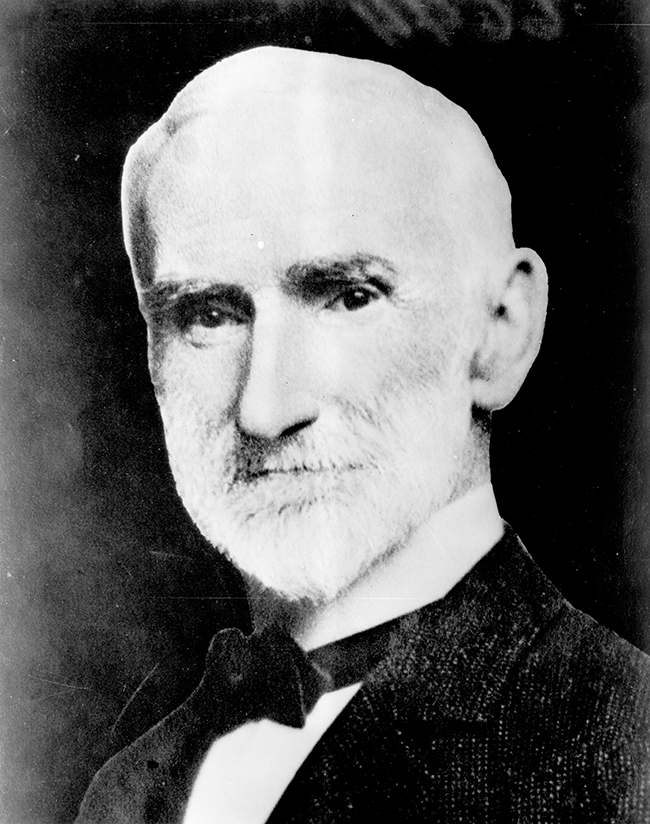

Though it was the San Fernando Valley they’d one day transform, these two Isaacs first met in another, faraway California valley. Tucked between the parallel ridges of the Vaca Mountains north of San Francisco lies Napa County’s Berryessa Valley. When Isaac Newton Van Nuys arrived in 1867, farmers had just begun tilling the valley’s broad plains, and the tiny farming town of Monticello had sprung up.

Born in 1836 to a family of Dutch farmers in upstate New York, Van Nuys split his childhood between summers on his father’s 500-acre farm and winters at public school. Even after finishing his studies, Van Nuys continued to work on the family farm through the age of 30, when his chronic asthma persuaded him to seek less arduous work in a sunnier climate.

Warmth and sunshine lured him to California, but Van Nuys—a born farmer—rejected the rough, urban edges of San Francisco. Instead he scouted nearby Napa County until the unplowed fields and unrealized potential of the Berryessa Valley drew him to Monticello. There, in the spring of 1867, he opened the town’s first general store.

The First Till

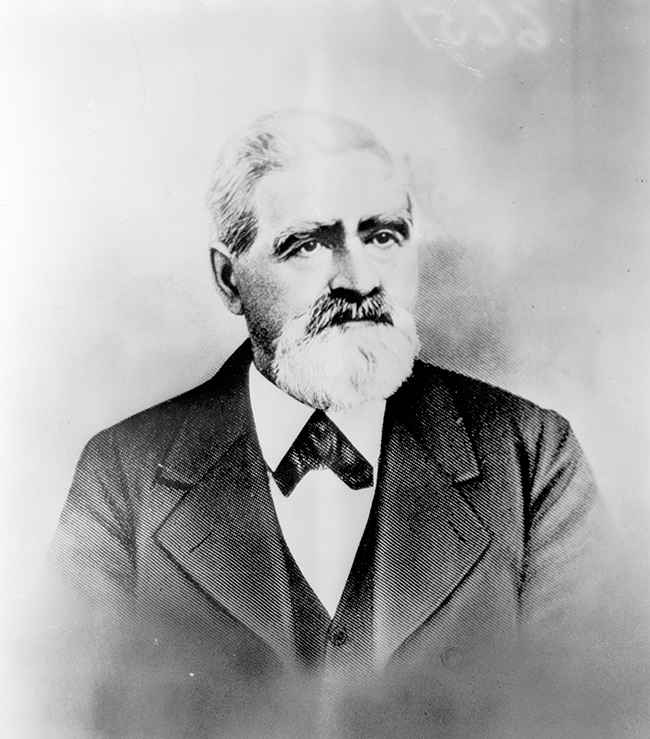

In 1854 Isaac Lankershim arrived in Napa County on horseback, his clothes dusty and his beard bushy and already fading to gray. Surrounding him was a large herd of cattle that he’d driven across the Great Plains, over the Rockies and through the desert from his ranch in Missouri. Lankershim’s wife, Annis, and children, Susanna and James, remained behind in St. Louis.

Years earlier as a teenager, Lankershim had made a similar solo trip, leaving his native Bavaria, where he was born in 1818 to a Jewish family, for a better life in the New World. In Missouri he made a small fortune shipping grain and livestock down the Mississippi River. Now in northern California, Lankershim hoped to leverage his wealth in a state where vast tracts of land—the old Mexican land grants, or ranchos—were up for grabs as tax bills and legal fees pried them from their original owners.

Inspired by the wild grain (likely wildrye) he saw growing, in 1855 he sowed and harvested 1,000 acres of wheat in Solano County—the first substantial wheat crop grown in the region. By 1867, when he stepped into Isaac Van Nuys’ general store in Monticello, Lankershim was one of California’s leading grain exporters.

The two men became fast friends, bonding over their common love of coaxing profits from the ground—and perhaps over their shared first name. So when Lankershim began to expand his agricultural enterprises—in 1868 he bought a large ranch near Fresno and the following year another in San Diego County—he turned to his new friend for help.

Lankershim needed someone to look after his farms in the northern part of the state while he traveled south. Van Nuys readily agreed. And it was while traveling among his various properties across the state around 1869 that Lankershim first set eyes on the San Fernando Valley.

Great Expectations

At the time, the Valley was a sparsely settled place. There was the former Mission San Fernando, where Andrés Pico—the Mexican commander who surrendered to the Americans at Campo de Cahuenga in 1848—had taken up residence. Pico’s hospitality was legendary. Guests at his adobe enjoyed lavish, six-course meals, and the aguardiente flowed freely.

At nearby Lopez Station, Wells Fargo stagecoaches stopped to deliver mail and passengers. Elsewhere, a few adobe houses dotted the plains or clustered around the springs at Encino. Otherwise the Valley was a shadow of its former self.

Most of its indigenous population had vanished. Some had fled the corporal punishment and forced labor that defined Indian life at the mission. Many others drifted away after the Mexican government abolished the mission system in 1834. A few remained, working as Don Andrés’ house-servants or tending to his livestock as vaqueros.

As late as 1862, massive herds of cattle—meat for the gold miners in Northern California—grazed the Valley floor. Then a severe, three-year drought desiccated the region and crippled the cattle industry.

Another animal—the sheep—began to fill the void as wool prices rose and the weather cycle swung back to wetter winters. And for Lankershim, there was an opportunity to profit from a Valley on the cusp of recovery.

Andrés Pico’s brother Pío, who owned half of the San Fernando Valley, was building a grand new hotel in Los Angeles and needed to liquefy his land holdings. Lankershim returned to the north to raise the requisite capital to buy Pico’s stake. Several San Francisco millionaires signed on, including Levi Strauss of blue jeans fame, and the San Fernando Farm Homestead Association was formed.

But when Lankershim stopped in Monticello to discuss the deal with Van Nuys, the conversation turned to something else: The same wild grain that had inspired Lankershim to raise wheat in Solano County also blanketed the vast plains of the San Fernando Valley. Perhaps wheat would take hold there too. Intrigued, Van Nuys agreed to join Lankershim as an investor.

On July 2, 1869, the association purchased 59,500 acres of the Valley—a huge swath of land that extended from the Simi Hills in

the west to the Burbank city limits in the east … and from the crest of the Santa Monica Mountains in the south to Roscoe Boulevard

in the north—for $115,000. Pío Pico used the proceeds to build the Pico House hotel, a building which still stands today near Olvera Street.

Seeding the Business

Isaac Lankershim immediately moved to his vast new ranch to oversee operations himself. The sale had included a flock of sheep, and now Lankershim sought to build a return on his and his partners’ investment.

At first, success. Ample rain ensured plenty of wild grass for feed, and wool prices held firm. The San Fernando Farm Homestead Association promptly renamed itself the San Fernando Sheep Company to reflect its confidence in the sheep-raising business. By 1873, as many as 40,000 sheep grazed the area.

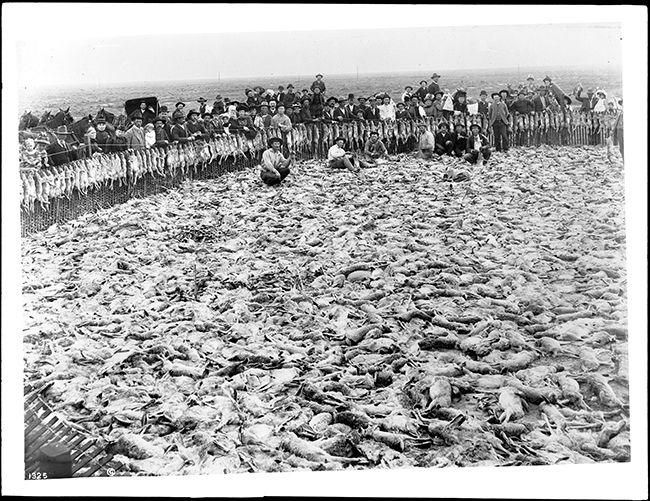

Then drought returned. After two years of dry weather, sheep-raising was ruined. One settler, Isaac Ijams, claimed that he “could have walked across the Valley on the bones of sheep and cattle.”

Fortunately, the San Fernando Sheep Company had diversified. Isaac Newton Van Nuys had sold his store in Monticello and moved south in 1871. While assisting Lankershim with the sheep business, Van Nuys fenced in a part of the pastureland and began planting fields of wheat, barley and other grains.

If successful with his experiment in dry farming—sowing the wheat and relying on the Valley’s rainfall rather than irrigation—Van Nuys could extract far greater profits from the land than he could by raising livestock. But others had already tested the idea.

If successful with his experiment in dry farming—sowing the wheat and relying on the Valley’s rainfall rather than irrigation—Van Nuys could extract far greater profits from the land than he could by raising livestock. But others had already tested the idea.

“So many ranchers had again and again unsuccessfully experimented with wheat in this vicinity,” Harris Newmark later wrote in his memoirs, “that failure and even ruin were predicted by the old settlers.”

In fact, Van Nuys’ wheat farming almost did fail thanks to the same drought that claimed so many sheep between 1874 and 1875. But he persisted.

By 1876, the rain returned, and Van Nuys’ experiment yielded enough wheat to ship two full cargoes to the global grain market in Liverpool. Lankershim and Van Nuys soon carved their vast holdings into six ranches dedicated to wheat farming—each with a tiny ranch house bobbing on the sea of grain.

Building an Empire

From afar, the Valley may have resembled a sea of gold, but converting those 60,000 acres of wheat into the real thing took a lot of coordination—and some inspiration. Van Nuys personally supervised the farming operations. Every month he would drive a buckboard over the Cahuenga Pass from his home in Los Angeles and spend a week consulting with each of his foremen.

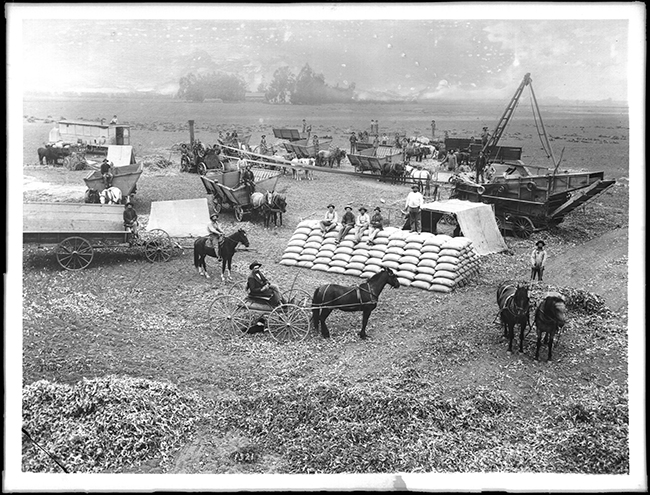

Seven giant combines worked continuously from May through November to reap, thresh and winnow each year’s crop. At first the two Isaacs shipped the grain to distant markets, where it was sold and ground into flour. But Lankershim soon realized that they could maximize profits by processing some of their harvest locally.

If wheat-growing was Van Nuys’ grand contribution to the joint enterprise, wheat-processing was Lankershim’s. In 1878, the two men purchased an old Southern Pacific rail depot in Los Angeles and built a gristmill there.

Soon the San Fernando Sheep Company earned a new name: the Los Angeles Farming and Milling Company. In 1888 alone, the mill processed 510,000 bushels of wheat. Lankershim and Van Nuys had built an empire.

Sealing the Deal

But the two Isaacs were more than business partners; ultimately they became family. In 1880, the Lankershim and Van Nuys families were united with the marriage of Isaac Newton Van Nuys to Susanna Lankershim, daughter of Isaac Lankershim.

It is tempting to speculate about their relationship. Did Van Nuys actually fall in love with the boss’ daughter? Or was it merely a marriage of convenience—simply another example of Van Nuys’ shrewd business instincts?

The historical record doesn’t give a definitive answer, but there are reasons to think the marriage was more a practical arrangement than anything else. Susanna and Isaac had known each other for at least nine years when they wed, and by 1880 she was 34 and he 45.

And just two years after the wedding, Van Nuys would inherit (through his wife) one-third of Lankershim’s substantial fortune. By the standards of its time, it was a successful union—one that produced three children.

And how did Susanna feel? “Mrs. Van Nuys told me that when she married Mr. Van Nuys, she made up her mind to do what he told her to do and that she had always done it,” an amateur historian recalled in 1944. “The plan apparently worked well, for they were happily married.” Marriage has changed since 1880.

Diverse Endeavors

Though for both men the San Fernando Valley was the one great project of their lives, they found time for other pursuits—especially as the continued success of their ranching and milling operations made them two of Southern California’s wealthiest businessmen. By 1880 both Isaacs had moved from the Valley to LA, then a middling settlement of only 11,000.

The younger Isaac’s fortune helped capitalize two local banks, and in his later years Van Nuys became vice president of the Farmers and Merchants National Bank of Los Angeles, still in business to this day. He also invested in a brick company and financed the construction of two buildings in downtown LA: the Van Nuys Hotel (now the Hotel Barclay) at Fourth and Main and the I.N. Van Nuys Building at Seventh and Spring.

Lankershim never branched out as much as his son-in-law, but he did find fellowship in Los Angeles’ Jewish community—even though he had renounced his faith long before. When he married Annis in 1842, Lankershim adopted the faith of his wife: Baptist Christianity.

His conversion was apparently sincere. For a long time he served as a deacon at a San Francisco church, and in his later years he gave generously to Baptist causes. Yet he kept close ties with family members who were active members of their synagogue.

His conversion must have been the subject of many whispered conversations around town, but according to historian David W. Epstein, LA’s Jewish community accepted Lankershim as one of their own. “He was a regular guy as far as they were concerned—with a quirk,” Epstein said in a phone interview. “After all, he looked Jewish, and he probably had an accent too.”

Lasting Legacies

Lankershim’s death in 1882 from the effects of stomach cancer raised doubts about the future of the two Isaacs’ operation. For a time, the San Fernando Valley ranch remained whole thanks to Isaac and Susanna Van Nuys’ marriage.

But eventually a real estate boom made the ranch’s land too valuable to devote exclusively to bonanza farming. In 1888 Isaac Lankershim’s other heir, his son James, purchased the ranch’s easternmost 12,000 acres and carved the great tract into small farms of 10 to 80 acres each.

A town soon rose near the center of the subdivision around the old San Fernando Road, which cut a diagonal path through the Valley. The town, known at first as Toluca, today forms the nucleus of North Hollywood.

Its main street, the old San Fernando Road, still exists today. James renamed it after his father: Lankershim Boulevard.

The Modern Valley is Born

James Lankershim’s land deal was only a preface to what would become one of the largest real estate subdivisions in Los Angeles history. In 1909 construction of the Owens Valley aqueduct was underway, and an investment syndicate comprising some of Los Angeles’ most powerful men—including the Los Angeles Times’ Harrison Gray Otis and Harry Chandler and electric railway baron Moses Sherman—knew that imported water would soon allow a city to bloom in the semiarid Valley.

They formed the Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company and made an offer. Van Nuys’ health, meanwhile, was failing, and both his family and his investors favored a sale. And so in September 1909, Van Nuys sold the remaining 47,500-acre ranch to the syndicate for $2.5 million, or $50 per acre.

Isaac Newton Van Nuys died on February 12, 1912. The Times announced the cause of death, cryptically, as “nervous prostration”—the catchall medical term of the era.

A Final Glimpse

Just as the ranch’s new owners began extending streetcar lines and automobile roads through the ranch, carving the wheat fields into the first towns—Owensmouth (today Canoga Park), Marian (now Reseda) and Van Nuys—an English writer and photographer rode through the Valley on horseback.

“It opened before me in league on league of grain, waving ready for harvest, a crop to be measured by the thousands of tons,” wrote J. Smeaton Chase in California Coast Trails. “The landscape flickered under an ardent sun, and as we plodded hour after hour along the tedious straight roads, escorted by clouds of pungent dust, I panted for the clean, crisp breezes which I knew were blowing just beyond.”

Change was coming.