A Long Time Ago in a Warehouse Far, Far Away

As Star Wars continues to dominate the box office, industry vets wax nostalgic about making the original movie in the Valley in the ‘70s.

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byMichael Goldman | Illustrated

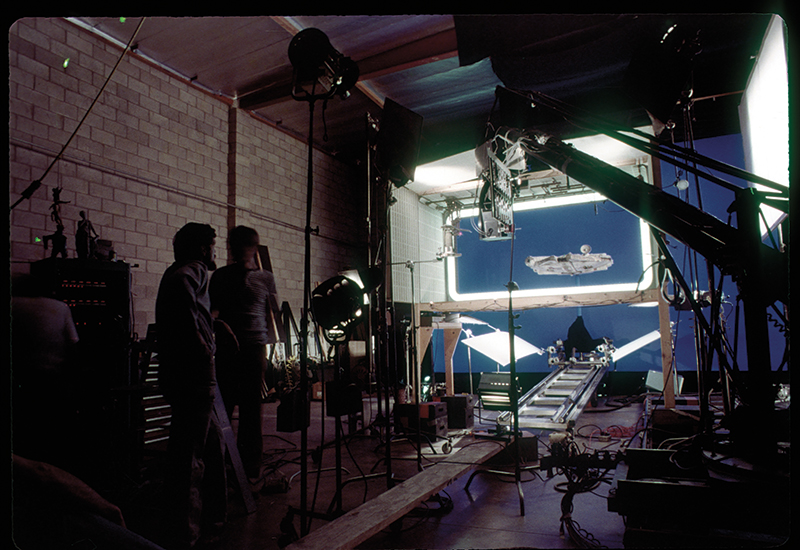

While the rest of the galaxy kvells over Star Wars: The Force Awakens, its humble beginnings trace back to a nondescript industrial warehouse in Van Nuys. That warehouse, located at 6842 Valjean Avenue, is today home to an architectural signage company. But back then, a little-known director named George Lucas was the tenant. Lucas filled the building with a group of young visual effects wizards and set them loose pioneering new techniques for the original 1977 classic Star Wars.

Lucas eventually moved his operation to the Bay Area, and it evolved into the legendary Industrial Light & Magic, although some key players stayed behind to work at the now-defunct visual effects company, Apogee Inc., which took over the site. Others shifted into the building next door to work for another Star Wars veteran, Grant McCune, at McCune Design—which still exists today.

The boss at the Van Nuys operation, John Dykstra, and his right-hand man, Richard Edlund, went on to become two of the most highly regarded and decorated artists in the medium’s history and are still active today. Here the two, along with former colleague Dave Berry, reminisce about making the movie that revolutionized the movie industry and kicked off one of the most successful franchises in history.

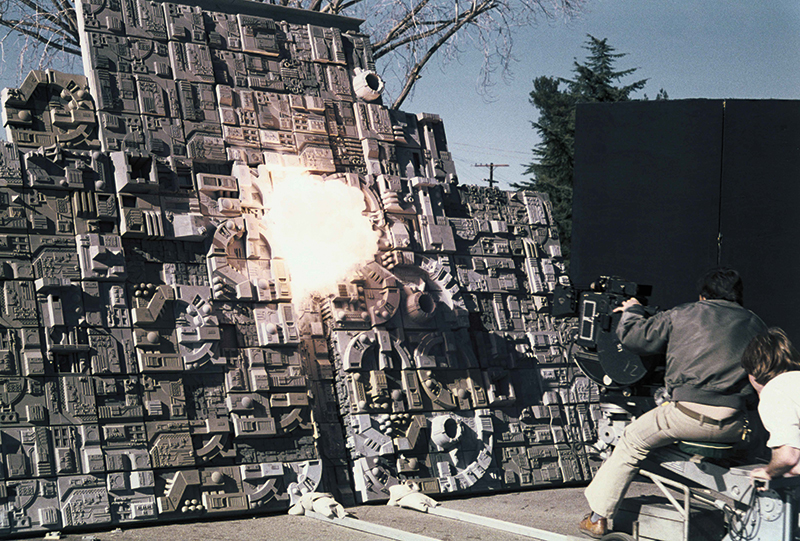

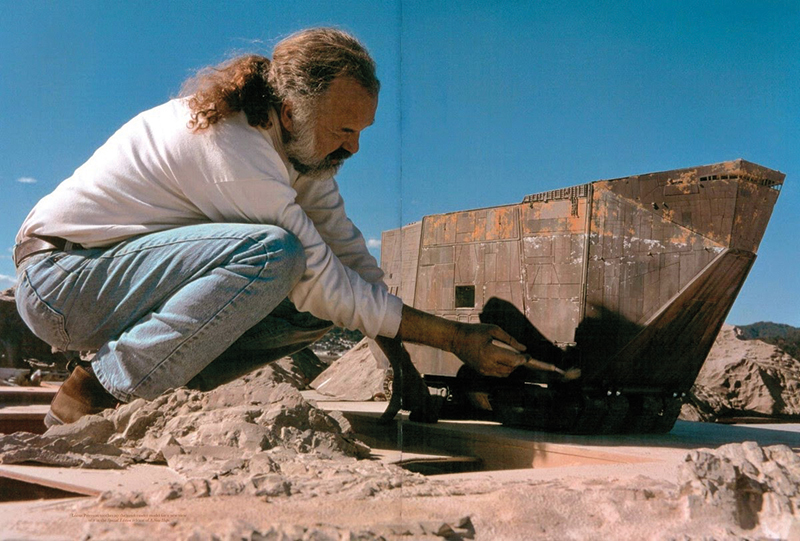

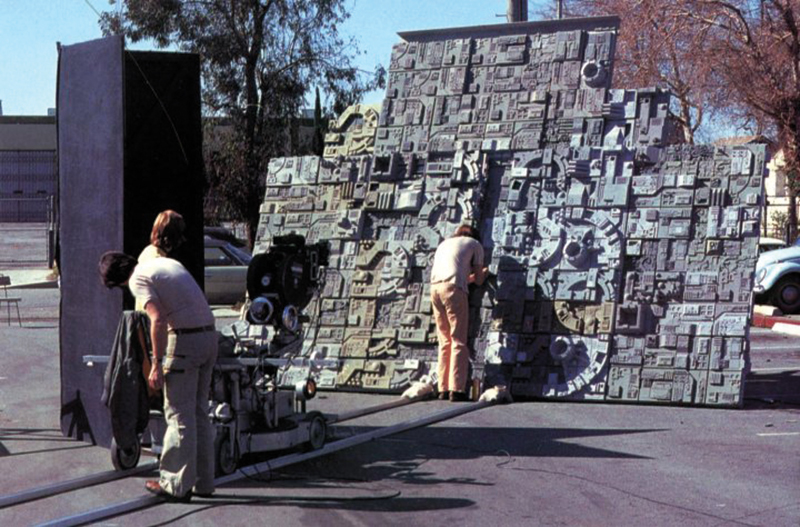

Pyrotechnics: In the winter and early spring of 1977, the production team at the Valjean facility began blowing up models in the parking lot.

John Dykstra

John Dykstra, a 35-year Valley resident, won an Oscar for his work on the original Star Wars. As production ramped up, he organized what he calls the “super garage” at Lucas’ behest.

“George Lucas and Gary Kurtz wanted that was not hidebound by tradition, because one of the problems was that to do the kind of visual effects that Star Wars needed, they had to have a moving camera. There really wasn’t a facility or a group that existed at the time suited for doing the kind of photography we wanted to do, so I brought the group together out of people I knew from around the industry, many of whom were good friends.

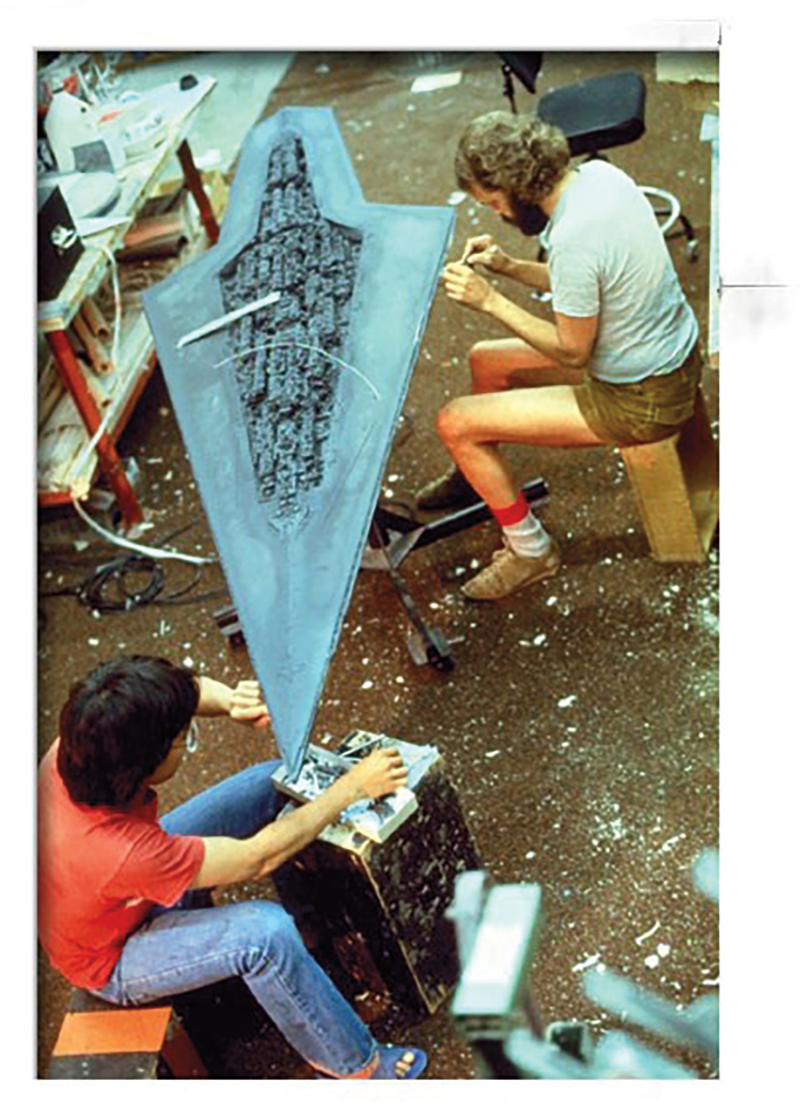

“We needed a large industrial space that could double as a stage with an open, clear span and accessible to all the kinds of technologies and services available in the Valley. So we found the space on Valjean. It definitely wasn’t a corporate organization. It was a super garage, where we had people of various talents coming together—machining, design, model makers, photography, lighting, chemical processes, optical printing. It was a real cross section and microcosm of the work going on in Hollywood at the time.

“We had positive pressure air conditioning in the optical department that we had a vendor set up like a clean room with a filtration system that blows particulate back away when you open the door of that department. But the rest of the place was really hot, which was one reason we often shot at night as much as we did. It got up to 120º to 130º on the stages because of the bright lights we were using.

“Because we worked at night, I think that is why the place got a reputation of being some kind of country club. People at the studio called it that, but those guys weren’t there at 11 at night when we were shooting on stage. Yes, we had a hot tub in the parking lot filled with ice water, but that was because it was 100º on stage. It was laissez-faire in that respect. But if you look at the product and the amount of time we put into it, that shows up on the screen. We took a lot of risks and went out of the box. Fortunately all our major bets were successful.”

Richard Edlund

Richard Edlund was one of Dykstra’s initial hires, summoned to perform acts of what he calls “weird photography” on the show. He also scored Oscar gold for the original Star Wars, as well as for The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Edlund now heads the Academy’s Scientific & Technology Council. He points to the creative laboratory in Van Nuys as the place where he had “the most incredible experiences of my life.”

“When I arrived, there was little more than a card table and a telephone inside. But I always felt confident about what the team was doing—I never doubted our ability. Basically we built a violin, and then we learned how to play it. We never thought we couldn’t do it.

“It was great because a real bonding took place as everyone put their best ideas forward. But we did get this reputation for being the clubhouse. That was completely unfair, because we typically worked 10-hour days at least. Yes, we wore shorts—even bathing suits—but that was because there was no air conditioning. And that’s why, when they made the big hot tub into a cold tub, I thought it was a great idea.

“I also remember one of the guys going to a surplus place and finding one of those escape slides for airplanes. You filled it up with air, and it looked like a hot dog—about 40 feet long. They set it up so that everyone who wanted to could slide down the thing . One time I was inside shooting elements for a visual effects shot, and everyone was outside in the afternoon sliding down the thing. And who shows up in a limousine but some studio executives, and they started to get the wrong idea. But they couldn’t have known. It was an incredible experience, and some of the things I learned there, I still use to this day.”

Dave Berry

Dave Berry spent most of his time running the optical printer during the making of Star Wars. He had the foresight to routinely bring his still camera and occasionally his 8mm film camera to work. In fact, he made a video with some of the material, which can be seen at vimeo.com/5494280. Berry, who won an Oscar for his visual effects work on Cocoon, says he sometimes regrets that “my film makes it seem like we were always partying, because everyone was very dedicated. I mainly got the camera out for birthday parties, and so the home movie is all that stuff strung together.

“I remember being very nervous all the time handling the original negative, putting it in a camera or projector. Just the idea that it could get dirty or scratched while I was handling it made me very nervous—accidents could happen. I don’t remember anything catastrophic, but mishandling a piece of film shot in England could get you fired. We were always battling to keep everything clean.

“And that could be difficult in that facility. I remember at one point we had a flea infestation. I think that came because people were always bringing their dogs, sitting on the ratty furniture they got from Goodwill in the screening room. And we had a mouse infestation also.

“There was no kitchen—we used to go to a place around the corner called Lumber Burgers, a fast-food place on the cross street just south of Valjean, and sometimes a Mexican place on Van Nuys Boulevard. But I don’t really remember getting out in the Valley too much when we were working. By my third week, I was working close to 80 hours a week—it was crazy. But we did have a coffee machine below the stairs, and inevitably every night someone would make coffee and then leave just a little bit in the machine with the burner left on, and it would burn out. One very distinct memory I have is the smell of burned coffee just permeating the entire building. someone would yell, ‘who left the coffee machine on again?’”