Shane’s Story

In a series of events kicked off by a supposedly harmless contraceptive drug, Shane would lose her health, her baby and her life. Here Shane’s family shares the full story in the hope that it, along with their new foundation, will save lives.

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byLinda Grasso

In July of 2009, Shane Gold Burwick was on top of the world. Newly married, the Sony Pictures executive discovered she was pregnant. Just six months later, in a series of cataclysmic events kicked off by a supposedly harmless contraceptive drug, Shane would lose her health, her baby and ultimately her life. She was 31.

In July of 2009, Shane Gold Burwick was on top of the world. Newly married, the Sony Pictures executive discovered she was pregnant. Just six months later, in a series of cataclysmic events kicked off by a supposedly harmless contraceptive drug, Shane would lose her health, her baby and ultimately her life. She was 31.

Here Shane’s family shares the full story for the first time in the hope that it, along with their new foundation, will save lives.

Shane’s older sister, Robyn Fener, also seated at the table, watches silently. Roberta continues, “There are so many pictures of her with mobs of Valley girls. She was always the most vivacious—the life of the party.”

After a deep breath, Robyn speaks. “She went to Vanderbilt. She loved to travel. She was unassuming, a bright light, sharply funny and perceptive. We had a bond that required no words to communicate.”

A LIFE INTERUPTED

As Robyn tells it, when Shane discovered she was pregnant that summer five years ago, she was still on something of a high—the kind of surge one gets after surviving a potentially fatal health scare. Robyn had always shared a love of baking with her younger sister, and one day—about a year and a half earlier—Shane had come to Robyn’s Sherman Oaks home to bake.

She mentioned that one of her legs was swollen. Robyn called a cardiologist friend who advised Shane to go to the closest emergency room. It was good advice.

The swelling turned out to be a deep vein thrombosis (blood clot) that reached Shane’s lung, causing a life-threatening pulmonary embolism. Blood thinners and anticoagulants were prescribed, and after a two-week hospital stay Shane was released.

“A few months later she turned 30, and we all celebrated,” Robyn recalls. “We thought she’d dodged a big bullet, and we said, ‘Well, we got through the worst—and now things can return to normal.’”

HOUSE OF CARDS

HOUSE OF CARDS

In an effort to explain what happened next, Roberta draws a parallel to a collapsing house of cards. She says the initial push—the thing that caused the very first card to fall—was the oral contraceptive Yasmin.

At the time of the blood clot, Shane had been taking Yasmin, one of several contraceptives that contain drospirenone, a newer generation of synthetic progestins. The popular drug (according to the Associa-ted Press, Yasmin and related drospirenone-containing pills were Bayer’s second-best-selling franchise in 2010 at $1.6 billion in global sales) has been the target of several studies over the years that have linked it to a higher risk of blood clots.

One study, funded by the FDA in 2011,suggested a 1.5-fold increase in the risk of blood clots for women who use birth control pills containing drospirenone compared to users of other hormonal contraceptives.

Dr. Waleed Doany is a Tarzana-based fetal-maternal specialist who focuses on high-risk cases and has been in practice for nearly 30 years. He never treated Shane but has discussed her case extensively with the family. “Yasmin was the product that caused Shane to have a blood clot,” he says.

While it was unknown at the time, doctors now believe Shane was probably born with a hereditary predisposition for blood clotting. And according to current label warnings, with that high risk factor she never should have been prescribed Yasmin.

THE SECOND HURDLE

By the summer of 2009, the blood-clotting incident felt behind her. In July, Shane discovered she was pregnant. The family, which included her new husband, Jordan, was over the moon.

Even though Shane was never officially diagnosed with a clotting disorder, the risks to her health at that time increased. “Once a women has a blood clot while on oral contraception, her risks are increased many-fold during pregnancy and the postpartum for having blood clots,” Dr. Doany explains.

He adds, “Pregnancy induces an increase in the proteins that encourage blood clots to form.” The OB-GYN describes it basically as a natural occurrence to protect the mother at delivery.

In November the couple flew to Boston to spend the holiday with Jordan’s parents. While there Shane started phoning her mother, complaining about unrelenting, debilitating headaches.

Back on the West Coast, the headaches continued, and all the while Shane was complaining to her doctors. After six weeks, they ran some tests. It was bad news: Shane had developed a clot in her brain.

Shane was hospitalized for two weeks, during which she received higher doses of blood thinner intravenously. Then suddenly, on New Year’s Day, she was released.

“Her OB-GYN said, ‘The baby is fine.’ And the neurologist said in three months, by the time of the birth, the CVT (blood clot in the brain) should be dissipated,” Roberta remembers.

THE HOUSE COLLAPSES

At nearly seven months pregnant, Shane was “tired, but doing great,” according to Robyn. But on January 11, 2010, a concerned Shane called her sister. “I don’t feel the baby moving,” she said. “I’m going to go to Cedars and get checked.”

At nearly seven months pregnant, Shane was “tired, but doing great,” according to Robyn. But on January 11, 2010, a concerned Shane called her sister. “I don’t feel the baby moving,” she said. “I’m going to go to Cedars and get checked.”

Shane’s suspicions were accurate. The baby was not alive. The treatment Shane had received was not enough to prevent the fetus from being affected. None of Shane’s doctors had realized the serious risk to her baby, who died due to severe clotting in the placenta.

Instead of aborting the fetus, Shane’s doctors performed a C-section, a surgery that would require Shane to go off her blood thinners. If the house of cards had been falling one at a time, the full-scale collapse was about to begin.

With every passing moment, Roberta sensed increasing danger. From her daughter’s bedside, she and her attorney husband, Arnold, started seeking answers—frantically calling each of Shane’s doctors.

Should she be having the C-section? What are the dangers, given her blood-clotting history? How long is it safe for her to be off her medication? “No one was connecting the dots,” concludes Roberta.

The C-section was not performed until Tuesday night. “They waited 36 hours to begin the surgery. I called everyone I could get a hold of. We couldn’t reach the neurologist; he was out of town. No on-call neurologist was ever sent. We were desperate to stay ahead of the game,“ Roberta recalls.

Shane would be off blood thinners for 56 hours, ultimately causing the brain clot to become massive.

THE HAIL MARY

After the surgery, Shane complained of extreme pain as blood clots multiplied in her brain. Roberta describes the period as “a slow-motion train wreck … At every turn there was not just one alternative that doctors could have chosen but several.”

By that time, according to Roberta, Shane’s doctors had left the hospital. “We were screaming in the hall for hours and hours, saying Shane needed help. There was no anesthesiologist, hematologist or neurologist. Everyone was gone.”

As the family tells it, it was Robyn who discovered what was to be the coup de grace. By then her sister was in a coma.

“I noticed swelling under her eye. I said, ‘She’s had a stroke!’” Robyn says, her head in her hands. “Finally, doctors performed a Hail Mary surgery.”

It was too late. That Thursday, January 14, Shane Gold Burwick died.

THE AFTERMATH

The family firmly believes Shane’s death was preventable. “A CVT (brain blood clot) has a 95% cure rate. Hillary Clinton had one. This is not something you die from! Shane died because her doctors ‘forgot’ for 56 hours

that she needed anticoagulation,” Roberta says. Robyn adds, “There was just such arrogance. There are a half-dozen specialists out there who would have known exactly what to do.”

The family points to Dr. Doany as one of them. “I thought Shane was getting the best care possible by going over the hill. I had no idea that I had the answer in Tarzana not three minutes from my Encino home,” Roberta says in frustration.

Dr. Doany agrees that, ultimately, Shane died because she was off blood thinners for too long. But he points out that there were other contributing factors including what he describes as inherent flaws in the American health care system. The first has to do with lack of communication.

“Sadly, in the U.S., patients with private insurance who are managed by great individual doctors may end up with worse care than indigent ones because the private doctors are not all on the same medical record, and they rarely ever have conference calls with each other for serious updates,” says Dr. Doany. “This is a chronic problem.”

The second flaw, according to Dr. Doany, is the tendency of doctors to stick to standard medical practices, based on test results “no matter what,” instead of seeking alternatives.

And the third problem, Doany points out, is inattention to detail. “In Shane’s situation, the doctor went for a lower dose of blood thinner and when she complained of persistent headaches, no investigation was initiated until it was unfortunately too late.”

Dr. Doany was one of several well-regarded specialists whom Roberta contacted in an effort to understand what exactly happened to Shane and how it might have been prevented. Others include Dr. Michael J. Paidas, based at the Yale School of Medicine and author of The Placenta: From Development to Disease; Dr. Robert Silver, chief of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Utah Health Sciences Center; and Dr. Andra James, who founded the Women’s Hemostasis and Thrombosis Clinic at Duke University.

Roberta, who is now something of a “walking encyclopedia” on the very latest research on maternal-related blood clotting, and Dr. Doany both maintain that had Shane received a higher dose of blood-thinning medication from the beginning of pregnancy, and had doctors used fetal monitoring techniques to detect fetal clotting issues, both Shane and her baby might have survived.

THE SHANE FOUNDATION

After Shane’s death, Roberta was wracked with anger and grief. She blamed Shane’s doctors and herself.

She’d spend hours in her house researching everything she could about Yasmin, blood-clotting disorders and the effect they can have on fetuses and pregnant women. Armed with a barrage of newfound knowledge, the family filed six medical malpractice lawsuits against five individual doctors and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

And the family continued to monitor the consolidated mass action lawsuit against Bayer, in which Shane had become a plaintiff—as one of tens of thousands of women who had taken Yasmin and suffered serious side effects.

As the litigation matriculated through the system, Roberta embarked on her next project. With Arnold as co-founder, Robyn as executive director and Dr. Doany as medical advisor, in 2013 the family formed The Shane Foundation, aimed at raising awareness of and supporting research for the prevention and treatment of contraceptive- and pregnancy-related clotting disorders.

What happened to Shane is very rare. The likelihood of a thrombus (blood clot) resulting from taking most oral contraceptives is below 1%. Roberta accepts that.

What she found harder to stomach were some of the statistics she discovered. “The U.S. is one of the only countries in the world where maternal deaths are on the rise. It is unacceptable. And one of the biggest causes of maternal death is pulmonary embolism. Shane had a brain blood clot during pregnancy. That is so well-treated in places like India.”

Roberta was also struck by another discovery: the high number of recurrent miscarriages in the U.S. One recent study indicates 500,000 women suffer recurrent miscarriages each year.

She was equally as taken aback by the number of recurrent miscarriages caused by blood-clotting disorders. One study she shares indicates that number might be as high as 55%.

What really affirmed that she was on the right track in forming a foundation was the fact that Shane exemplified all three major blood-clotting issues that affect women and babies: those due to oral contraceptives, those that adversely affect babies and those that cause maternal death. “It’s a major women’s health care issue,” she notes.

The real game changer for the nonprofit was when it forged a partnership with the March of Dimes, getting the longtime organization to expand their website to more clearly explain maternal-fetal clotting disorders. Together, the two organizations have developed a pamphlet that spells out the disorders. And they are working to get OB-GYNs to put it in their offices—making the information easily accessible to expectant mothers.

“We want to encourage a dialogue. We want women to read the pamphlet and ask their doctors questions,” says Roberta.

The foundation also aims to raise research money to develop better screening tests for blood disorders. Shane was tested, but the results came back negative.

The situation seems to be akin to how we went about treating breast cancer 20 years ago; we know what some of the dangerous genes are—but not all of them. A negative test result simply says a patient does not have what he or she was tested for.

THE SETTLEMENTS

In coping with the tragedy, the foundation has been a godsend for the family. The litigation, on the other hand, was something they simply felt they had to do. The lawsuits against Cedars and two of Shane’s doctors were ultimately settled out of court.

Regarding the mass action consolidated lawsuit, Shane’s case was included in one of the first groups to get a settlement from Bayer. In 2012 the FDA updated the warning label on Yasmin stating that users may be three times as likely to develop blood clots.

THE FUTURE

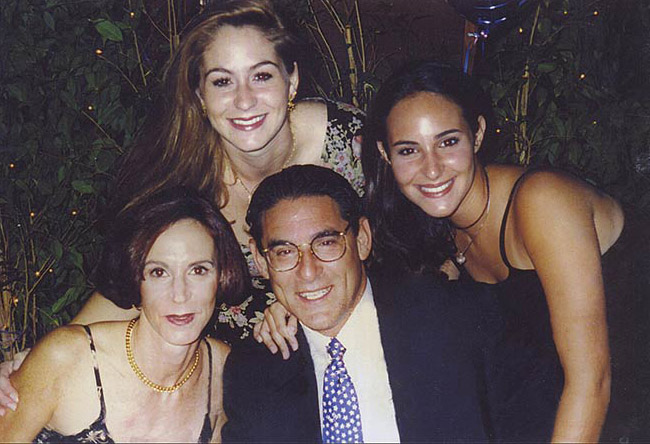

Roberta and I see each other again in late September, when this story is just about written. We have met to scan some family photos to run with this piece. Normally photos are dropped off and returned, but I sense these images are just too precious.

She urges me to select photos of Shane that “really look like her.” The snapshots show more carefree times of the handsome Gold foursome traveling the world and on special occasions.

It’s hard not to notice how much weight Roberta has lost. As the machine hums, I pepper her with a few remaining questions and then apologize—concerned it may be too taxing. After all, we were just supposed to be choosing photos on this day.

“Oh no,” Roberta remarks, staring me straight in the eye and blinking back tears. “I love talking about Shane. I want to keep talking about her. For me, it keeps her alive.”